Why does knowledge sovereignty matter? What recent policy developments may be used to enhance it? While the barriers are real and the stakes are high, this opening chapter next situates climate change as a strategic opportunity not only for Tribes to retain cultural practices and return traditional management practices to the landscape, but for all land managers to remedy inappropriate ecological actions, and for enhanced and successful collaboration in the face of collective survival. The second portion of the chapter reviews recent and promising Federal policy developments, many of which are referenced in the recommendations sections of chapters to follow.

Lavern Glaze sharing knowledge with youth. Photo: California Indian Basketweavers Association

Knowledge Sovereignty: What is at Stake?

Amidst the great and welcome interest in Tribal traditional ecological knowledge by the wider non-Tribal community lies a thorny problem: how can TEK be applied to the landscape without risking what is most sacred to Tribes? Unfortunately the loss of control of Tribal ideas and information poses a serious problem for the Karuk Tribe and beyond. It is critical for any individual or agency entity seeking to fulfill their public and Tribal trust responsibilities as federal administrators, to collaborate with Tribal managers or to engage traditional Tribal knowledge to understand this terrain. A number of excellent resources detail how cultural differences, power relations, the romantization of indigenous knowledge and the all too frequent de-contextualization of indigenous knowledge have worked together to perpetuate Native knowledge extraction as an ongoing aspect of cultural genocide (Tsosie 1996, Simpson 2004, Bowery and Anderson 2009, Jones and Jenkins 2008, Heckler 2012). Museums have centrally functioned in these negative outcomes (Lonetree 2012). The recent emphases by Universities to copyright research materials poses an immediate threat to collaboration. Discussions in Chapter Two on cultural differences in the nature and use of knowledge, as well as discussions in Chapter Three on inadequate protections of Tribal knowledge will also be of use in illustrating this process in action.

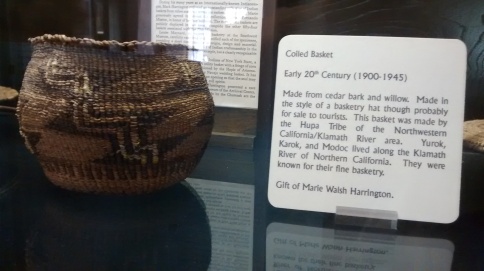

Basket held in the San Fernando Mission Museum. Photo: Klamath-Salmon Media Collaborative

It has been said that if one looks at the arc of colonialism in North America, colonial power in the 1700 and 1800s was mobilized through the direct taking of lives and land from Native people, during the 1800s and 1900s colonialism operated through the usurpation of minerals and lands, and for the most recent fifty to one hundred years colonialism has operated via the extraction of Native knowledge. While the connection between knowledge extraction and genocide is very real, the extraction of knowledge and ideas from Tribal communities looks very different than other forms of “taking” or “harm.” This fact has created great confusion on behalf of non-Native agency members and research scientists concerning the seriousness of the situation. Unlike the “taking” of life, land and mineral wealth, in most cases knowledge is taken by “well meaning” people who are trying to “do the right thing.”

It is important therefore to offer a deeper explanation of how the Native knowledge systems are damaged by non-Native agencies, scientists and other actors. Mechanisms of cultural appropriation that erode Tribal knowledge sovereignty will be elaborated in Chapters Two and Three. Fundamental differences in understanding of the nature of knowledge between Native and Western worldviews, differences in the organizational capacity between Tribes and other management actors, and (often unconscious) underlying beliefs in the superiority of Western worldviews all work in the present day context alongside more overt institutional barriers to the enactment of traditional management to erode knowledge sovereignty.

Knowledge is fundamental to management that itself is an expression of culture. Knowledge sovereignty is an extension of cultural, social and political sovereignty. Part I of this report details the relationship of knowledge sovereignty to Native subsistence economies, cultural and spiritual practices, cultural identity, physical health and psychological well-being. We recommend further reading of the excellent and detailed literature on the central role of Western science in the project of colonialism and the corresponding ethical risks Native communities face (Bannister and Hardison 2006, Hansen and Van FLeed 2003, Hardison and Bannister 2011, Hill et al 2010, Janke 2009, Williams and Hardison 2013, Colorado and Collins 1987, Agrawal 2002, Briggs and Sharp 2004, Briggs 2005, Green 2004, Heckler 2012, Nadasdy 2003, Roy and Bicker 2000, Watson-Verran and Turnball 1995, Wildcat 2009), the ethical risks for Tribes from engaging in research with non-Native entities (Baldy 2013, Williams and Hardison 2013, Hill et al 2010, Hardison and Bannister 2011, Hansen and Van Fleed 2003, Bannister and Hardison 2006) and unfortunately, the ongoing ways that the extraction of Tribal knowledge perpetuates cultural genocide today (see also Norgaard 2014 for more detail specific to Karuk land management struggles).

Climate Change as Strategic Opportunity

“Tribes have much to offer in helping to find solutions to the pressing challenges confronting our nation’s forests. Tribes have developed and practiced resource management strategies over thousands of years of experiential learning and have adapted to changing conditions in local ecosystems. Tribes historically managed forests, woodlands and grasslands of North America using a wide array of tools to sustain ecosystems and their communities. Fire (natural and anthropogenic) historically played a predominant role in maintaining ecosystems of culturally desired plant and animal habitats (biodiversity). More recently, Tribes have adopted western science to complement indigenous knowledge and experience as they adapted management philosophies to changing societal conditions.”

— Intertribal Timber Council 2013, 7f

The threats that American Indian Tribes face in relation to climate change are many. Shifts in the populations of traditional foods and cultural use species, changes in the quality and abundance of those species, and even in ongoing cases, the need to relocate as island and other habitats are eroded by changing patterns of ice and sea level rise, all pose profound challenges for Tribal people (Bennett et al 2014, Figueroa 2011; Lynn et al. 2011; Shearer 2011; Voggesser 2013; Wildcat 2009). Kyle Powys Whyte (2013) describes how, at base, climate change threatens the “collective continuance” of Tribal peoples: “These challenges lead many tribes to remain concerned with what I call collective continuance. Collective continuance is a community’s capacity to be adaptive in ways sufficient for the livelihoods of its members to flourish into the future” (518).

While Native people encounter unique and often particularly urgent threats in the face of climate change, all peoples and all ecosystems around the world are at risk. Climate change evokes an urgent need to rethink many aspects of western social, economic and political systems, including western land management practices. In this moment of crisis, new possibilities for cooperation have emerged. There is a new awareness for the need to share information. Agencies are trying to work together to think about climate change – a problem that does not follow bureaucratic lines. Government agencies, the western scientific community and non-profit land managers alike have begun to point to the importance of returning to traditional management practices (see footnote 4).

As dangerous as it is, we can thus understand the present moment as one of strategic opportunity. Kathleen Pickering Sherman and her co-authors write “The increasing pressures of global ecological crises demand that the potential of indigenous ecological knowledge be explored to restore socio-ecological resilience into natural resource management” (2010, 508). The Intertribal Timber Council (2013) writes

“Tribes, states and federal agencies collectively recognize the need to address growing threats through collaborative efforts that cross forest ownership boundaries. Insect and disease outbreaks are occurring at an unprecedented frequency and scale. Wildland fires are increasing in duration and size. These challenges are further compounded by climate change, increasing land fragmentation from residential, rural, and urban development; and loss of the infrastructure necessary to provide economic benefits essential to the ability to maintain working forests on the landscape; help sustain forest-dependent communities; and reduce costs of treatment to restore forest health and ecological processes” (7).

Legal scholar Mary Wood closed her recent address to the 2014 Tribal Environmental Leaders Summit with this statement”

“We have arrived at an unthinkable moment in time, where entire food groups are contaminated, water carries poisons, and global climate disaster threatens to destroy nearly all of Nature’s Trust. The consequences to society from actions taken by this generation of people are profound. We need all of the will and wisdom we can muster to rise to this moment. This will and wisdom will not come from the culture that brought us this crisis. Tribal leaders can voice responsibilities that echo back through millennia. They have perhaps never been heard at a more crucial time. As my colleague, Rennard Strickland, wrote, “If there is to be a post-Columbian future – a future for any of us – it will be an Indian future . . . a world in which this time, . . . the superior world view . . . might even hope to compete with, if not triumph over, technology.”

The Karuk and other Tribes across the country are working to identify how the broader interest in Tribal knowledge and practice from multiple management agencies and the general public can be mobilized in service of these mutual goals. On the mid-Klamath region in northern California where there exists an extreme threat of increased trends in fire frequency and severity in the context of climate change, the Karuk Tribe is uniquely positioned to employ knowledge and management activities that will benefit both Tribal trust and public trust resources. Many goals in the US Forest Service’s own management plan can be best achieved through recognizing the Tribal right to management. Karuk traditional knowledge can be leveraged to restore and maintain fire resilient landscapes and achieve cohesive strategies for wildland fire management. At this juncture it is however critical that the Karuk and other Tribes in similar situations retain sovereignty over TEK, not only for Tribal interests, but in order to attain the ecological outcomes desired by all.

Beyond the issues of justice, sovereignty public trust or human rights discussed in this report, there is now a growing recognition that American Indian Tribes and Tribal management techniques are often the most effective mechanism to achieve many aspects of public land management desired by all agencies. Especially in the face of climate change, enabling Tribes’ abilities to use traditional management techniques may be the best way for agencies achieve their own goals on issues as diverse as protection of the wildland/urban interface, to providing habitats for fish, wildlife, and plants, combating incursion by invasive species, and supporting local economies. This is so not only because Tribes have proven techniques for maintaining ecological conditions in the face of intensive fuel loading and past wildfire suppression, Tribes frequently also have less bureaucratic structures than other agencies. Tribes have existing authorities for many management actions under shared jurisdiction within existing Federal trust responsibilities that ought to be more fully implemented. In other cases, it will be necessary to increase Tribal authority within the Federal structure.

“Tribes are in a unique position to press for management actions to protect their rights and interests given the fiduciary trust responsibility of the United States and authorities such as the Tribal Forest Practices Act. As political sovereigns, Tribes are able to practice stewardship and apply traditions, practices, and accumulated wisdom to care for their resources, exercise co-management authorities within their traditional territories, and strongly influence and persuade other political sovereigns to protect natural resources under the public trust doctrine”

— Intertribal Timber Council 2013, 15

The Karuk Tribe has been struggling to maintain knowledge of and the ability to carry out traditional management techniques since the arrival of non-Native settlers. Interest in Tribal TEK creates a relatively supportive political environment that can be conducive to a return of traditional management activities – thereby benefitting Tribal culture, non-Indian people and forest ecosystems.

Recent Initiatives Providing Platforms To Enhance Knowledge Sovereignty

A number of recent legislative actions, policy documents, resolutions and legal developments hold promise for providing platforms for the retention of knowledge sovereignty. Many of the initiatives introduced here form groundwork for the development of recommendations as they apply to the specific barriers to knowledge sovereignty that are detailed in Chapters Two and Three.

United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The opening of the 2007 United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognizes “that respect for indigenous knowledge, cultures and traditional practices contributes to sustainable and equitable development and proper management of the environment.” More specifically, Article 31 section 1 concerns the fact that:

“Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.”

And Article 11, 2 indicates:

“States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs.”

While UN Resolutions are non-binding agreements, the fact that the United States has endorsed this Declaration can be a useful leverage point for Tribes seeking to return Tribal management to landscapes.

National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy

Extreme wildfires in the west in the 2008 fire season led to the passage of the 2009 Federal Lands Assistance and Management Enforcement Act or “FLAME Act” that in turn led to the development of the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy (NCWFMS) NCWFMS is a “collaborative effort of diverse Tribal, federal, state and private stakeholders working to develop an effective plan to address our nation’s wildland fire and forest health concerns.” Each of the three key inter-related goals of the NCWFMS — restoring and maintaining resilient landscapes, creating fire-adapted communities, responding to wildfires, provides a context and foundation for the protection of knowledge sovereignty, and the expansion of Tribes’ abilities to manage in “off reservation” lands. For example, one key recommendation of the NCWFMS is to “Expand collaborative land management, community and fire response opportunities across all jurisdictions, and invest in programmatic actions and activities that can be facilitated by Tribes and partners under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Act (as amended), the Tribal Forest Protection Act, and other existing authorities in coordination with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” (2012, 5).

The NCWFMS acknowledges the significance of indigenous management of the landscape, and that its absence is both an ecological concern and a treat to indigenous cultural identity. Further specific items within these efforts such as the emphasis on “Community Wildfire Protection Plans” where communities and community values may be defined at the local level, an emphasis on “middle lands” or “middle ground,” areas between wildland-urban interfaces and “backcountry” as an area of concern for fuels treatments, and a clear emphasis throughout written materials on coordination and cooperation between entities including Tribes, and the need to find new avenues to achieve the above are each potential leverage points for the expansion of Tribal knowledge sovereignty through the management of off reservation lands. For example, according to Phase III of the National Cohesive Wildland Management Strategy Regional Science-Based Risk Analysis Report (2012) “Adjacent counties, states, tribes, and municipalities should share information and coordinate plans across boundaries for a seamless approach to wildfire planning” (80).

The 2012 NCWFMS also contains language that may be useful for expanding the range of federal contractual options: “Federal end-result contracts, compacts and/or agreements can be entered into by Tribes, communities, states, and for-profit or non-profit organizations to conduct fuels and restoration activities on nearby BLM or Forest Service lands” 2012, p. 33. Similarly, the fact that Phase II of the National Cohesive Strategy for Wildland Fire Management requires use of the most “effective combination of agreements, contracts and compacts” to conduct a wide range of activities from management to planning or re-assessment may provide an avenue for the expansion of Tribal management. Chapter Three will discuss how these efforts can be used to overcome institutional barriers to the expansion of Tribal management.

1994 Tribal Forest Protection Act and

2013 Effectiveness Review by Intertribal Timber Council

The Tribal Forest Protection Act, P.L. 108-278, (TFPA) was enacted in 2004 following intense wildfire activity in the West. The TPFA was specifically designed to reduce institutional barriers to Tribal “off reservation management” in order to protect Tribal trust resources from fire, disease and “other threats coming off of Forest Service or BLM lands” and to offer a mechanism for collaboration to address climate change on Tribal lands (Voggesser et al 2013, 623). The TPFA authorizes the Secretaries of Agriculture and Interior to give consideration to Tribally- proposed stewardship contracting or other projects on U S Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands bordering or adjacent to Indian trust land. As noted by the Intertribal Timber Council “Tribes have reserved rights to fish, hunt, and gather on millions of acres of land administered by the Forest Service. Tribes are becoming increasingly concerned that deteriorating conditions on Forest Service lands threaten their ability to protect on-reservation resources held in trust by the United States on their behalf and to exercise reserved rights“ (ITC 2013, 2).

“In recognition that the United States has a fiduciary trust responsibility to protect Tribal lands, resources, and rights, the TFPA enables Tribes to propose projects to address hazardous conditions on lands administered by the FS and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which border or are adjacent to Tribal trust lands or resources. The TFPA could facilitate treatment and collaboration between the FS, Tribes and BIA to manage and restore healthy forests on the landscape“ (ITC 2013, 2).

However, a recent review of the effectiveness of the Act by the Intertribal Timber Council and the U.S. Forest Service notes that in the nearly 10 years the Act has been in place only six successful projects, accounting for less that 20,000 acres have been completed. The authors conclude: “The promise of the TFPA to provide a means for Tribes to work with federal agencies to restore forests and reduce forest health threats at a landscape level remains unfulfilled” (2013, 3). The Act as well as the Intertribal Council “Fulfilling the Promise Report” that evaluates it are each useful tools for engaging cultural barriers discussed in Chapter Two and the institutional barriers that will be discussed in Chapter Three.

Executive Order 13175:

Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments.

In November of 2000 President Clinton signed Executive Order 13175 on

Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments. This order establishes that “agencies shall adhere, to the extent permitted by law, to the following criteria when formulating and implementing policies that have tribal implications:

(a)Agencies shall respect Indian tribal self-government and sovereignty, honor tribal treaty and other rights, and strive to meet the responsibilities that arise from the unique legal relationship between the Federal Government and Indian tribal governments.

(b) With respect to Federal statutes and regulations administered by Indian tribal governments, the Federal Government shall grant Indian tribal governments the maximum administrative discretion possible.

(c) When undertaking to formulate and implement policies that have tribal implications, agencies shall:

(1) encourage Indian tribes to develop their own policies to achieve program objectives;

(2) where possible, defer to Indian tribes to establish standards; and

(3) in determining whether to establish Federal standards, consult with tribal officials as to the need for Federal standards and any alternatives that would limit the scope of Federal standards or otherwise preserve the prerogatives and authority of Indian tribes.”

2009 Omnibus Act

The 2009 Omnibus Act authorizes the transfer of funds from the U S Forest Service appropriations budget, to the Department of Interior. From there funds could be transferred directly to a specific Tribe for the purpose of wildland forest management thereby enabling Tribal access to needed economic resources for utilization of traditional management. Material below is quoted from 123 STAT. 733 On “WILDLAND FIRE MANAGEMENT (INCLUDING TRANSFERS OF FUNDS)

“for necessary expenses for forest fire pre-suppression activities on National Forest System lands, for emergency fire suppression on or adjacent to such lands or other lands under fire protection agreement, hazardous fuels reduction on or adjacent to such lands” and “Provided further, That the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture may authorize the transfer of funds appropriated for wildland fire management, in an aggregate amount not to exceed $10,000,000, between the Departments when such transfers would facilitate and expedite jointly funded wildland fire management programs and projects.”

The ability to directly transfer funds to Tribal budgets is an important mechanism to achieve the important goal of expanding collaborative land management. This mechanism to enhance tribal management is especially beneficial in light of limits in Tribal capacity as discussed in Chapter Three.

Tribal Authority and The Clean Air Act:

Western Regional Air Partnership Join Forum on Fire Emissions.

The 2005 Western Regional Air Partnership Joint Forum on Fire Emissions relates to Tribal Authority under the Clean Air Act. This document contains guidance on categorizing natural vs. anthropogenic emissions sources, and identifies a process for classifying Tribal cultural burns as a natural emissions source along with wildfires (prescribed fire is an anthropogenic source). The categorization of Tribal cultural burns for maintenance purposes as natural means that Tribes do not need to obtain permits or to conduct planning to carry out cultural burns, thereby alleviating the costly and bureaucratic barriers that presently reduce Tribe’s ability to use often limited resources in the most effective manner (see Chapter 3). As Bill Tripp, Karuk Department of Natural Resources states “Once forest stands are restored to the condition that you are looking for, a pre-European condition, then you can use prescribed fire to maintain that” This key document has the potential to be a powerful tool for maintaining Tribal sovereignty regarding use of fire and expansion of TEK in the landscape but has yet to enter policy or regulation. The formal adoption of this idea into policy and regulation would also serve as explicit acknowledgement of Tribal sovereignty and jurisdictional authority over air resources.

Public and Tribal Trust Litigation

“As the original sovereigns on this continent, tribes represent the original trustees. Their remarkable long-term stewardship of resources – sometimes sustained over the course of millennia – provides a supreme example of ecological fiduciary care.”

-Mary Christina Wood, 2014, 14

Tribal trust is “a principle that arises from the Native relinquishment of land in reliance on federal assurances that retained lands and resources would be protected for future generations. It bears rough analogy to nuisance and trespass law. Ownership of land carries corollary rights of government protection-the right to seek judicial redress against harm to property. The Indian trust responsibility is protection for property guaranteed on the sovereign level, from the federal government to tribes” (Wood, 2003). Through their legal scholarship Mary Wood and other legal scholars stress the importance of reminding government decision makers of their legal obligations as fiduciaries (see also Peevar 2009, Tsosie, 2003, 2013). The concept of tribes as co-trustees or co-tenant of natural resources also exists within what is known as the public trust framework.

In the Pacific Northwest treaty fishing cases, courts have recently described Tribes and states as analogous to “co-tenants” of a common asset (their shared fishery).[1] Using the same logic, we could think of Tribes as co-trustees with respect to all shared resources, including migratory fish and wildlife, atmosphere, and waters that flow off the reservation. . . . The Ninth Circuit, after characterizing the Tribes and states as “co-tenants” in the fishery, said,

Cotenants stand in a fiduciary relationship one to the other. Each has the right to full enjoyment of the property, but must use it as a reasonable property owner. A cotenant is liable for waste if he destroys the property or abuses it so as to permanently impair its value. A court will enjoin the commission of waste. By analogy, neither the treaty Indians nor the state on behalf of its citizens may permit the subject matter of these treaties to be destroyed (as quoted in Wood 2014, p. 15).

Just as they have with the case of the shared fishery of the Columbia River Basin, Tribes can assert their standing as co-tenants of water, forests and more. But because they are not currently recognized, these rights must be asserted through legal action. Such developments would assist primarily with the institutional barriers described in Chapter Three.

2013 Creation of White House Council on Native American Affairs and Interagency Memorandum of Understanding on Sacred Sites and Sacred Landscapes

The 2013 creation of the White House Council on Native American Affairs, and the 2012 interagency Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on the protection of Indian Sacred Sites are important events in the pathway toward indigenous knowledge sovereignty. This landmark Memorandum of Understanding is designed to strengthen the protection of Indian sacred sites. It was signed by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and four cabinet-level departments (the Department of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Interior). The MOU commits the participating agencies to “work together on developing guidance on the management and treatment of sacred sites, on identifying and recommending ways to overcome impediments to the protection of such sites while preserving the sites’ confidentiality, on creating a training program for federal staff and on developing outreach plans to both the public and to non-Federal partners.” This MOU may be useful in addressing institutional barriers to Tribal management as discussed in Chapter Three.

Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges in Climate Change Initiatives

In 2014, an ad hoc group of Tribal leaders, Tribal scholars and others came together in response to a request from the Department of Interior Advisory Committee on Climate Change and Natural Resources Science to develop “Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges in Climate Change Initiatives.” The Guidelines is an informational resource for Tribes, agencies, and organizations across the United States with an interest in understanding traditional knowledges in the context of climate change. The purpose of the Guidelines is to provide foundational information on the role of traditional knowledges in Federal climate change initiatives, to describe the principles of engaging with Tribes on issues related to traditional knowledges, and actions for Federal agencies and Tribes to consider that will establish processes and protocols to govern the sharing and protection of traditional knowledge. The Guidelines are intended to foster opportunities for indigenous peoples and non-indigenous partners to braid traditional knowledges and western science in culturally-appropriate and Tribally-led initiatives. These Guidelines will be especially useful in addressing many of the cultural barriers to traditional management and knowledge sovereignty discussed in Chapter Two.

Recent National Congress of American Indian Resolutions

Seven recent resolutions from the National Congress of American Indians outline key issues regarding knowledge sovereignty and native management and may provide leverage points for action.

1) Resolution #REN-13-035, 2013 Request for Federal Government to Develop Guidance on Recognizing Tribal Sovereign Jurisdiction over Traditional Knowledge

This resolution references and builds up Article 11, 2 of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that: “States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs.” Language in the resolution refers to problems in cultural and other differences in the appropriate use and relationship of people to knowledge and calls for the Federal government to work with Tribes to develop appropriate guidelines:

“WHEREAS, the emphasis on the utilization of traditional knowledge should focus on support for its application by tribes to solve environmental and climate problems without the need for sharing it; and WHEREAS, in those cases where traditional knowledge may be shared by the tribes, measures need to be developed to ensure that it is used appropriately, that tribes are protected in policy and law against its misuse and that the tribes are able to determine and receive benefits from its use; and NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that the Federal government work with tribes to develop appropriate guidance on how to approach tribes for access to traditional knowledge, while also respecting the right of each tribe to develop its own terms of access; and WHEREAS, the emphasis on the utilization of traditional knowledge should focus on support for its application by tribes to solve environmental and climate problems without the need for sharing it; and WHEREAS, in those cases where traditional knowledge may be shared by the tribes, measures need to be developed to ensure that it is used appropriately, that tribes are protected in policy and law against its misuse and that the tribes are able to determine and receive benefits from its use; and NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that the Federal government work with tribes to develop appropriate guidance on how to approach tribes for access to traditional knowledge, while also respecting the right of each tribe to develop its own terms of access; and NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that the Federal government work with its funding agencies to ensure respect for and protection of these rights in all federally-funded projects;”

2) #REN-13-065 Protection and Preservation of Culturally Significant Sites, Areas, and Landscapes

Note that this resolution cites the 2013 creation of the White House Council on Native American Affairs and the recent interagency MOU on the protection of Indian Sacred Sites, which is also referenced in the prior section.

WHEREAS, the June 26, 2013 Executive Order established the White House Council on Native American Affairs and under section 3(e), such Council shall coordinate its outreach to federally recognized tribes through the White House Office of Public Engagement and Intergovernmental Affairs; and . . . WHEREAS, the United States has committed to honoring the government to government relationship between Native American Tribes and the federal government and ensuring that treaty obligations are met; and relationship with Indian Country, four cabinet-level departments joined the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation in releasing an action plan to strengthen the protection of Indian Sacred sites, and provide greater Tribal access to their heritage area. The interagency plan is required by the Memorandum of Understanding signed in December 2012 by the Department of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Interior and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation regarding coordination and collaboration for the protection of sacred sites; . . .

NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that NCAI urges the United States government under the MOU’s participating agencies engage in a meaningful review to expand the 106 process in all permitting to include the option of sacred site regional impacts; and that the 106 be expanded to have the capacity to stop a permitted project that will destroy sacred sites that include the ancestral Treaty fishing and hunting and gathering rights, indigenous inherent rights and resources, life way, and will destroy sacred places, areas, landscapes, waterways and their commitment to:

- New development of energy that the MOU provides a clear recognition and address a plan with tribes impacts one treaty over another treaty right, as well as any other federal right that may be impacted by the energy development, transportation and exportation based on the impact to sacred sites, areas, landscapes, and seascapes.

- Sustainable stewardship and protection of their traditional lifeway.

- Long-term protective management of these landscapes and seascapes

- Promoting Tribal unity and defeating the efforts of outside companies or agencies to divide the tribes against each other.

- Preservation, protection and application of traditional knowledge and resource management systems to the natural environment assumes and assures a sustainable yield;”

3) #TUL-13-006 Requiring a Federal-Tribal Joint Review of Sacred Places Taken Away from Native Peoples

“NCAI calls on the President to direct federal entities to review and report on the manner in which they’ve acquired jurisdiction regarding Native American sacred places and whether such jurisdiction was asserted and sacred places taken with or without Native peoples’ free, prior and informed consent, and whether the federal government disposed of sacred places or turned over control of them to others with or without Native peoples’ free, prior and informed consent; and BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that federal entities, in collaboration with the Native nation(s) with traditional religious interest in the sacred place, prepare recommendations for protection of the sacred place, through existing laws and policies, through a federal-Tribal agreement to co-manage or jointly steward the sacred place, through transfer and return of the sacred place to the Native nation(s), or through a mutual agreement to seek congressional approval of a plan to protect the sacred places; and BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that this directive be issued as quickly as possible, so that this federal-Tribal collaborative work may begin to rescue sacred places from ongoing or pending desecration;

4) National Congress of American Indians (2012). Resolution #LNK-12-023. Federal Investigation of Observance of Federal Trust Responsibility to Protect Native American Ancestral Lands and Cultural Resources.

This resolution calls for more accountability concerning the state of Federal encroachment on Native sacred sites, the gathering of data on the state of the problem via formal investigation by the Government Accountability Office into civil and criminal protections to protect Indian nations from “encroachment onto sacred sites” and for the drafting of Congressional legislation to protect Tribes from various levels of intrusion into sacred sites including more effective consultation. Some excerpts of the resolution are below:

NCAI hereby holds that Indian Nations are entitled to free, prior and informed consent of all actions, records and plans that may affect their sacred sites, air shed, water shed, natural resources, ancestral remains . . . BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the GAO and Congress work with the Indian Nations . . . to assist with outreach for data collection to all federally recognize tribes . . and BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the NCAI hereby insists that members of Congress draft legislation that allows tribes to (1) meet standing requirements, (2) obtain immediate restraining orders to halt noncompliant projects, and (3) be afforded the proper relief for civil and criminal damages when private or government actions, with or without full compliance with project impact assessments, cause irreparable harm to the integrity of ancestral lands and cultural resources of Indian Nations. . . . and BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the NCAI strongly urges Congress to immediately improve tribal consultation and BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that NCAI demands a more streamlined the processes in which Indian Nations interact with the federal government by incorporating the following:

– Increase authority, oversight and intervention by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP);

– Develop with the DOJ, DOI, EPA a jurisdictional trust responsibility to protect tribes from encroachment on their sacred sites, ancestral burial remains, air shed, water shed and natural resources

– Require tribal consultation prior to any cultural resources or archaeological research on all federal projects. . .

5) National Congress of American Indians (2010) Resolution #ABQ-10-086. Ensuring Tribal Equity in the Dept. of Interior’s Climate Change Adaptation Initiative.

This and the next two NCAI resolutions concern climate change specifically, underscoring the importance of traditional knowledge sovereignty in this context. Resolution #ABQ-10-086 focuses on the importance of Tribal participation in Federal climate adaptation activities. Of particular concern in this resolution is the lack of inclusion of Tribes in the Climate Change Adaptation Initiative that the Department of the Interior began in 2009 as a strategy for the nation to effectively help natural resources adapt to the impacts of climate change. The resolution calls for specific funding to go to Tribes for participation in this effort.

6) NCAI Resolution #PDX-11-036: Increasing Tribal Participation in Climate Adaptation.

Similarly to the resolution discussed above, this resolution calls for strong Tribal participation in the development of all policies for adaptation to climate change.

WHEREAS, climate change is a threat to American Indians/Alaska Natives’ culture, resources, and well-being that is currently impacting hunting, fishing, gathering, economic infrastructure, reservation locations, usual and accustomed areas and natural resources; and

WHEREAS, indigenous nations are in a unique and venerable position in regards to climate change, as their land bases provide few opportunities to relocate or expand or cope with changing climate; and WHEREAS, tribal rights established under treaties, executive orders and other legal instruments are fixed to specific parcels of land, so that it is unclear what tribal rights to resources might shift away from their reserved lands; and WHEREAS, furthermore, tribal rights to hunt, fish and gather that are established and guaranteed under treaties, executive orders, and other legal instruments may be rendered moot by these shifts, or may need to be adapted by transferring harvesting rights to non-traditional species; and . . . NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that the NCAI urges the United States, its agencies, scientists and all relevant organizations to include Tribes in all climate change policies, programs, and activities from the very start, and at all levels; and recognize and respect Tribal traditions, ordinances and expectations regarding access to and use of traditional ecological knowledge, based on prior and informed consent; and build and enhance Tribal capacity to address climate change issues; to provide adequate and proportional funding for Tribal climate change adaptation and mitigation; and consult with Native Sovereign Nations as decision makers with all policy, regulations and laws related to climate change effects on important tribal cultural, natural and sacred resources . . .

7) NCAI Resolution #REN-13-020: Adopting Guidance Principles to Address the Impacts of Climate Change.

This last resolution describes the need for NCAI evaluation of the effectiveness of the Executive Order 13175 on Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments and Secretarial Order 3289 Addressing the Impacts of Climate Change on America’s Water, Land, and Other Natural and Cultural Resources. The resolution also calls for the creation of Tribal Climate Change Task Force, made up of Tribal government representatives and others, in order to create and implement a plan of action regarding climate

. . . NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that NCAI commits to collaborating with ATNI to develop an action plan which lays guiding principles and action steps a to address the impacts of climate change upon tribal governments, cultures, and lifeways; that will protect and advancing our treaty, inherent and indigenous rights, tribal lifeways and ecological knowledge; and. . . BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that NCAI collaborates with ATNI and commits to create a Tribal Climate Change Task Force, composed of tribal governments, intertribal organizations, and non-tribal partners to develop and implement the plan of action . . .

This is not an exhaustive list, but taken together these recent policy developments, declarations, and NCAI resolutions provide a valuable foundation for actions to preserve Tribal knowledge sovereignty, advance Native land management and enact the application of traditional knowledge in the landscape. The next two chapters will describe the challenges Tribes face in maintaining sovereignty over knowledge and suggest how these and other recent policy developments may be used to leverage forward momentum.

[1] Puget Sound Gillnetters Ass’n v. U.S Dist. Court for W. Dist., 573 F.2d 1123, 1126 (9th Cir. 1978) (explaining that the treaty established “something analogous to a cotenancy, with the tribes as one cotenant and all citizens of the Territory (and later of the state) as the other.”).