The Karuk Tribe governs reservation and trust lands, tribally owned fee parcels and the rights and interests of the tribe and its members/descendants as it relates to the air waters, lands, plants, animals, and ecosystem processes within Karuk Aboriginal Territory. Managing for climate change requires long-term institutional capacity within the Tribe, yet climate change itself simultaneously holds the potential to undermine tribal capacity. Threats to Karuk program capacity resulting from the increased frequency of high severity fire occur in the context of the remote location and specific jurisdictional context of the Tribe. The Karuk Tribe is a self-governance Tribe, employing roughly ~231 staff and with an annual operating budget of ~$37 million.

The Karuk Tribe’s Panamnik Senior Center, Community Computer Center, Tribal Library, and Health Clinic. Photo: Stormy Staats, KSMC

The Tribe has developed programs, policies and departments to administer services to Karuk people and to uphold responsibilities to care for the land. The governmental structure includes nearly twenty departments, programs, and services organized into three service districts. The area is remote with a single major highway connecting the 120 miles along the Klamath river between these districts. Administrative offices, government operations and the Karuk People’s Center are located in Happy Camp, the Department of Natural Resources is located in Orleans and Somes Bar, and the Karuk Judicial System is located in Yreka. Health clinics, education and elders programs, housing authority offices, community computer centers, tribal court services, and human services/Indian Child Welfare programs are located in each of the three main population centers.

Tribal functions take place within an infrastructural context that includes power supplied by Pacific Gas and Electric in the Orleans community and Pacific Power in Happy Camp, water systems supplied by local municipalities (Orleans and Happy Camp), phone lines from Sisqutel and private satellite carriers, and highway maintenance by CalTrans and Siskiyou and Humboldt counties. In addition, the US Forest Service operates hundreds of miles of dirt roads in the region. A sizable section of Karuk ancestral territory is entirely off the grid (homes along roughly 60 highway miles through ancestral territory totaling 46 Karuk tribal members and descendants in 19 households).

While all tribal programs may face general impacts during high severity fires such as transportation interruptions, air quality impacts or power outages, all but one of the programs most directly impacted from the increased frequency of high severity fire are located within the Karuk Department of Natural Resources (KDNR). The 2015 KDNR Strategic Plan describes the history and the organization of the department as follows:

Founded with a single employee after Congressional appropriations were allocated to support fisheries management and the restoration efforts of the Tribe, DNR has grown into a multi-program department that has included over one hundred (100) employees during fire events – all sharing the common mission of protecting, promoting and preserving the cultural/natural resources and ecological processes upon which the Karuk depend. A focus of the department is to integrate traditional management practices into the current management regime, which is based on certain principles and philosophy. This is noted in the Department’s Eco-Cultural Resources Management Plan (ECRMP):

As guardians of our ancestral land, we are obligated to support practices that emphasize the interrelationships between the cultural and biophysical dimensions of ecosystems. The relationships we have with the land are guided by our elaborate religious traditional foundation. For thousands of years, we have continued to perform religious observances that help ensure the appropriate relationship between people, plants, the land, and the spirit world. We share our existence with plants, animals, fish, insects, and the land and waters. We are responsible for their well-being. Our ancestral landscapes overflow with stories and expressions from the past, which remind us of who we are and direct us to implement sound traditional management practices in a traditional and contemporary context.

In recent years the KDNR has successfully spearheaded the adaptation of the first Tribal Cultural Beneficial and Subsistence Uses for the TMDL process in the State of California, won litigation ending suction dredge mining throughout the State, and played a leading role in historic relicensing and settlement processes regarding the removal of four main-stem Klamath river dams. The Karuk DNR headquarters are located at 39051 Highway 96 in Orleans, with a workstation located eight miles upriver in Somes Bar and the office of the Sípnuuk Digital Library, Archives and Museum two miles downriver in Orleans.

Multiple Jurisdictions and Limited Recognition of Tribal Authorities

The Tribe operates within a complicated cross-jurisdictional terrain in which Karuk management authority is often unacknowledged and misunderstood. Federal non-Tribal management agencies are operating in Karuk territory include the US Forest Service,  Bureau of Indian Affairs, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Reclamation and the Environmental Protection Agency (which oversees State implementation of air and water quality). State and regional entities include California Fish and Wildlife Department, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE) and the Northwest Regional Water Quality Board. Most of the Karuk Tribe’s ancestral territory is within the National Forest System.

Bureau of Indian Affairs, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Reclamation and the Environmental Protection Agency (which oversees State implementation of air and water quality). State and regional entities include California Fish and Wildlife Department, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE) and the Northwest Regional Water Quality Board. Most of the Karuk Tribe’s ancestral territory is within the National Forest System.

Lack of recognition of tribal jurisdiction limits Tribal program capacity at multiple levels. On the day to day, this lack of recognition requires enormous staff time to engage in an often contentious manner with other entities, while in the bigger picture, it affects the Tribe’s ability to establish and maintain effective Tribal programs under the current budget formulas, laws and policies of the United States. While climate change, and here the effects of high severity fire in particular stresses the program infrastructure and capacity of the Karuk Tribe, the actions taken by these other entities during and after high severity fires can be as great or greater a problem for tribal program capacity as the fires themselves. Furthermore, the fact that tribal staff must work with two different National Forest  units who have had two very different approaches to forest management including fire also poses challenges to program capacity. Communicating and interfacing with so many agencies takes a great deal of time and effort, even under normal circumstances. In the context of climate change, meaningful engagement given current budgetary and staff constraints is often difficult, if not impossible. Climate change is rapidly reshaping the managerial and legal landscape, with the result being that multiple new agency plans and action items are put forward by new configurations of individuals and groups who may not have training or familiarity with tribal trust responsibilities. This situation puts tribal staff into defensive mode of responding to queries and projects coming from other entities regarding actions of their design. In addition, in the face of climate change agency actions come more often in the form of crisis situations that invoke emergency timelines and management protocol exceptions. Forest Service personnel in particular have frequent turnover and a tendency to make short-term decisions that have long-term adverse impacts. Bill Tripp included the following statement in his comments to the EPA Climate Change Adaptation Plan Webinar in 2012:

units who have had two very different approaches to forest management including fire also poses challenges to program capacity. Communicating and interfacing with so many agencies takes a great deal of time and effort, even under normal circumstances. In the context of climate change, meaningful engagement given current budgetary and staff constraints is often difficult, if not impossible. Climate change is rapidly reshaping the managerial and legal landscape, with the result being that multiple new agency plans and action items are put forward by new configurations of individuals and groups who may not have training or familiarity with tribal trust responsibilities. This situation puts tribal staff into defensive mode of responding to queries and projects coming from other entities regarding actions of their design. In addition, in the face of climate change agency actions come more often in the form of crisis situations that invoke emergency timelines and management protocol exceptions. Forest Service personnel in particular have frequent turnover and a tendency to make short-term decisions that have long-term adverse impacts. Bill Tripp included the following statement in his comments to the EPA Climate Change Adaptation Plan Webinar in 2012:

Typical agency turnover in Karuk country is also an issue. Hiring of agency positions in rural areas has a tendency to bring in employees that have never experienced the local situation. These individuals also have a tendency to remain in place for only a short period of their career. This imposes fundamental problems with the ability of a community in place to maintain a culture of intuitive interaction and learning throughout the landscape. Agency personnel have a tendency to make short-term decisions that have long-term adverse impacts for communities of place.

The KDNR has limited staff that can participate in these regulatory processes, and staff time for such engagement is not written into the deliverables of grants, which form the majority of KNDR funding.

Constraints of Project Based Funding

The fact that Karuk tribal jurisdiction is not recognized by all agency actors further limits capacity across a range of programs because BIA base funding availability is not scaled up to reflect the area that the Tribe seeks to manage. Whereas the Karuk Constitution is inclusive of all Karuk ancestral lands, according to the Indian Self Determination and Education Act, the formula used for funds allocation is based on a Tribe’s reservation land base. If however, the formula were calculated for a Tribe’s territory rather than a reservation it would enable the management of a much larger area. Instead, because much of Karuk DNR funding comes from grants there is no general funding for programs, staff must constantly chase down resources and there are limits in the flexibility of staff to respond in emergency scenarios or to take a proactive approach in response to issues that arise in the moment.

Impacts to Program Capacities During High Severity Fire Events

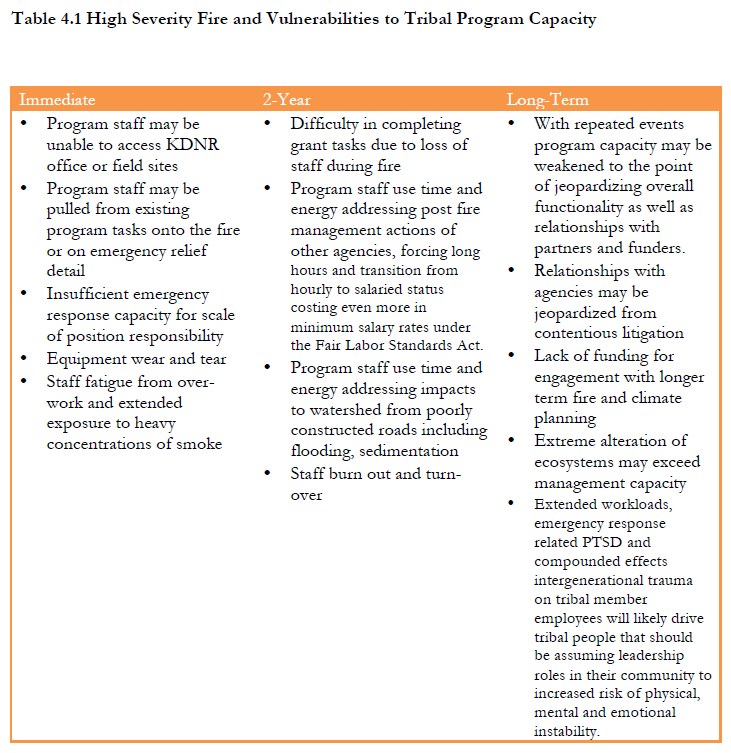

Karuk ancestral territory is a fire-adapted ecosystem. The presence of fire must be understood as a regular seasonal aspect of tribal operation and life. However, in the context of fire exclusion and the changing patterns of temperature and precipitation fires have significantly increased in severity and size. The average number of fires over 1,000 acres has doubled in California since the 1970s. Challenges to program capacity in the face of high severity fires then, occur in this general context. Challenges that are experienced across programs include loss of internal staff who are needed to participate on fires, difficulty reaching Forest Service staff who may also be out on fires, disruption of transportation routes, or the need to stay home from work in order to protect one’s own home. Staff from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and other agencies with fiduciary trust or other consultation responsibilities also go on fires causing additional layer of complexity in communication, coordination and consultation efforts. See Table 4.1 general descriptions of impacts common across programs. More detailed descriptions of impacts for specific programs are provided in the following sections.

“Everything seems to stop when we have a fire.”

Multiple people noted, “Everything seems to stop when we have a fire.” Diversion of staff resources and time in conflict and consultation over fire management decisions exacerbate existing institutional vulnerabilities, leaving fewer resources for progressing actions in positive, proactive directions (e.g. directions that builds upon traditional ecological knowledge, preserves living culture, and enables tribal members to serve a traditional role in a contemporary context).

Infrastructure Impacts During Wildfire Events

The function of tribal programs also requires reliance on infrastructure, including roads and utilities (water, power, telephone, internet), most of which are supplied by non-tribal entities. Karuk ancestral territory is mountainous with the transportation routes almost entirely constricted to the river corridor. Program capacity is often significantly impacted by loss of power and especially by disruption in transportation routes. Municipal water systems have been impacted during fire events and do not have adequate capacity. When one elder’s house burned down the town water supply was drained and the fire could not be put out. In the aftermath of the 2008 fires the Tribe instigated an emergency preparedness division which assisted with development of training a tribal Type 3 incident management team to handle Stafford act responses. This team was deployed in 2013 to set up an evacuation center and clean air center, but being grant funded the program disbanded after the two years of initial grant when continuation funding was not granted.

Emergency Management Mode

During fires, the decision-making process moves to a short timeframe and hierarchical structure in which NEPA is not required for significant management actions such as the use of fire for back burning or road building and cutting trees in riparian areas. Individuals within the U.S. Forest Service and California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE) make decisions with long-term consequences for the Tribe and ecosystem very quickly with little information about Karuk knowledge, values or presence. These individuals do not have long-term connections to the watershed, and base their decisions according to non-Tribal criteria. Actions in riparian and wilderness areas that are not normally allowed are given emergency exemptions. As a result of the imposition of this outside emergency decision making structure, significant tribal staff time and effort is spent responding to and “cleaning up after” actions taken as emergency measures such as restoring damage to streams from fire lines and road construction. In the words of one staff member “That the Forest Service gets to decide what is a crisis in general is a problem.” When asked how much program time is spent responding to decisions made during crisis situations, Karuk Tribe Fisheries Program Manager Toz Soto replied “almost all of it.” Decisions made by non-Tribal entities about what is to be protected and how to protect it—including the use of back burning, the creation of fire lines and the use of chemicals and fire retardants—require staff time and energy to respond to and diminish limited capacity within the Department of Natural Resources. Others have noted that as high severity fires happen with increased frequency, more planning should take place in advance: “Events that happen predictably every year shouldn’t qualify for emergency exemptions.” Instead, regulatory waivers should apply to the solution rather than the problem. Exposure levels mitigated or remediated, or otherwise balanced over time should be a measure of success in supplying such waivers.

Program Capacity in the Immediate Aftermath of Fires

In the aftermath of high severity fires, erosion, flooding and landslides from the fires or from poorly constructed roads may occur as increased sediment may cause landslides onto roadways. Mitigating this situation takes time and energy, especially from staff in the fisheries, transportation, and watershed restoration programs. Blocked travel routes can be very significant impacts to program capacity if people are unable to get to the workplace, or of those who work in the field cannot access field sites.

In addition, the actions of other agencies in the 1-2 year period after fires may require program staff intervention. This emergency management structure may be extended beyond the wildfire event, as occurred in 2016 when emergency water quality exemptions were requested and granted for salvage logging after the 2014 fire. In 2016, KDNR staff that were working on the proactive approach of the Western Klamath Restoration Partnership were pulled from this project to engage in litigation in an effort to protect tribally important species impacted by the Westsides timber sale. Such diversion of resources affects both program capacity and tribal management authority. Over time excessive workloads leads to staff burn out and turn over – a problem that has added challenges in the rural community where there are few people qualified or afforded the opportunity to gain the experience to do many important tasks.

Long Term Effects of High Severity Fire on Program Capacity

If program capacity has been severely weakened during and post fire events the overall functionality of programs may be jeopardized in a number of ways.  Whereas relationships and collaborations are needed more than ever in light of climate change, these relationships with other agencies, academic collaborators and funders may be impacted by contentious litigation concerning post fire management activities, or by unfulfilled grant deliverables and incomplete research data as a result of fire interruptions. Climate change in general and the increasing instance of high severity fire compels additional management planning, yet the limitations of grant funding structure make meaningful engagement in such activities nearly impossible. Severe alteration of the Klamath River ecosystem from repeated high severity fires could ultimately exceed the ability of the Karuk Tribe to manage.

Whereas relationships and collaborations are needed more than ever in light of climate change, these relationships with other agencies, academic collaborators and funders may be impacted by contentious litigation concerning post fire management activities, or by unfulfilled grant deliverables and incomplete research data as a result of fire interruptions. Climate change in general and the increasing instance of high severity fire compels additional management planning, yet the limitations of grant funding structure make meaningful engagement in such activities nearly impossible. Severe alteration of the Klamath River ecosystem from repeated high severity fires could ultimately exceed the ability of the Karuk Tribe to manage.

These are general capacity impacts faced by many programs as a result of high severity fire. In the next section impacts to Food Security, Transportation, Water Quality, Fisheries, Health, Integrated Wildland Fire Management, and Watershed Restoration Programs are addressed in more detail.

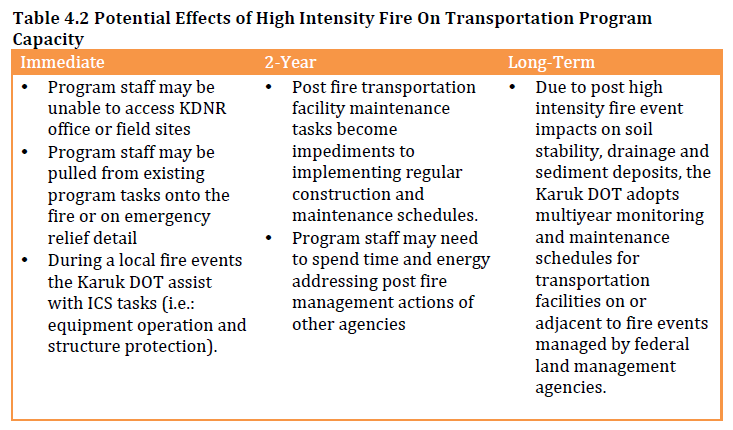

High Severity Fire and Vulnerabilities to Transportation Program

The mission of the Karuk Tribe Department of Transportation is to provide safe reliable transportation facilities for all users. The Karuk Tribe Department of Transportation (Karuk DOT) is funded through the United States Department of Transportation Tribal Transportation Program. In coordination with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Karuk Tribe, acquired funding and first established a Transportation Department in 1992. Throughout the years the Tribe has built a solid foundation for growth and in 2010 entered into a Tribal Transportation Program Agreement with the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). This agreement allows the Tribe to work directly with FHWA and receive federal funding for the administration of the Karuk Tribes Tribal Transportation Program (TTP). A prime objective of the TTP is to contribute to the economic development, self-determination, and employment of Indians and Native Americans.

The Karuk DOT is tasked with constructing and maintaining Tribal transportation facilities exclusively on Tribal Lands. Additionally, the Karuk DOT coordinates and partners with adjacent Federal, State and local agencies to ensure safe reliable transportation facilities for all user groups.

Traditional Tribal Transportation facilities are an important part of the transportation system; we recognize the river and tributary corridors, as well as, earthen foot trails as facilities that were principal means of village to village access, ceremonial needs, cultural resource utilization and commerce preceding European influx into Karuk ancestral territory. The Karuk Tribe is compelled to recognize social justice challenges that have impacted the Tribe since European influx; these issues are still ubiquitous today in the way of low economic opportunity, restricted access to traditional cultural resources, employment, schools, food sources, medical facilities, emergency evacuation routes. All forms of transportation are a vitally important to lessen the impacts from these challenges.

Today, state highways and county roads that traverse through Karuk ancestral territory are recognized as main access routes to population centers locally and regionally. While tribal, state and county transportation facilities are utilized within communities to provide access to general services, education, health services and employment, as well as, ceremonial needs and cultural resource utilization.

Although modern day transportation facilities provide general access, the Karuk people are stewards of this land with the inherent responsibility to pass on knowledge of and access to ceremonial sites, traditional foods and responsible cultural resource utilization. Karuk DOT is committed to scheduled assessments, maintenance and preservation of traditional tribal transportation facilities. Karuk ancestral territory is mountainous with the primary travel routes and only thoroughfare roads along the Klamath and Salmon River corridors. Highway 96 is the main travel route through approximately 72 miles of Karuk ancestral territory. This highway connects the region to Interstate 5 in the East and to Highway 299 to the southwest. The Salmon River Road begins in Somes Bar, traverses another 31.2 miles of road through Karuk ancestral territory and connecting to CA State Route 3 in Etna, CA, with connections to Interstate 5 and CA State Route 299. The Salmon River road is a one-lane route over much of its course. Multiple roads connect to the high country. In addition there are many logging roads maintained by the USDA Forest Service.

The increased likelihood of high intensity wildfire presents risk to travel throughout Karuk territory both due to direct Forest Service and California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE) road closures during fire events, and from flooding and landslides in the immediate (2 year) aftermath of high intensity fires. While these transportation closures may be relatively short term (in the period of days or weeks), transportation systems are especially vulnerable due to the steep forested topography and the fact that there may be no alternate routes for travel increases the severity of the situation. Road closures during wildfire events cut off the community from the outside, potentially affecting escape routes, access to emergency service and food supplies. In the aftermath of high intensity fires erosion, flooding and landslides may occur as increased sediment may cause landslides onto roadways. Blocked culverts may cause flooding as upstream flows accumulate behind the culvert. Culvert blockages from increased sediment may damage or destroy main travel routes, as well as travel routes into the high country.

Road managers within the Tribe and CalTrans already contend with these climate-related impacts. However climate change is expected to alter their frequency and intensity. Furthermore, as other climate related events such as flooding, storm surge and sea level rise become more severe, resources of agencies such as CalTrans are likely to be increasingly tapped, making it possible that services and repairs take much longer than usual. Rural regions are commonly under-served due to their low population sizes. Transportation vulnerabilities for the Karuk Tribal community may be further underscored by the fact that the 2014 CalTrans climate assessment for Humboldt County rated Hwy 96 region at middle point of criticality for roads in relation to climate change (2014, p. 2). While Highway 96 may not be the most vulnerable road in the county, this categorization is likely to mean that limited resources will be distributed to other road systems.

The increased likelihood of high intensity and severity wildfire may affect the Karuk Tribe transportation department in various ways. The potential effects of high intensity fire due to climate change are well noted as a priority concern by the Karuk DOT. As multiple routes traverse throughout the heavily forested Karuk ancestral territory, high intensity fire events create short term emergencies, while the impact of fire is long-term to community residents and their transportation facilities. The Karuk DOT recognizes our responsibility to the Karuk People in providing safe ingress/egress for general services, education, health services and employment, as well as, ceremonial needs and cultural resource utilization. We continue to diligently address increasing issues of climate change, as well as, the need for redesign of current transportation facilities with innovative low maintenance solutions to the impacts and aftermath of high intensity fire events Our ultimate all inclusive goals are to meet the mission of the Karuk DOT in providing safe reliable transportation facilities for all users. During fire events road closures may occur depending on fire location. Working with a small obsolete heavy equipment reserve the Karuk DOT is still compelled to assist in evacuations and emergency service ingress/egress. To ensure timely accomplishment of emergency tasks new more efficient equipment is greatly needed. Additionally and although not funded, the Karuk DOT must develop and adhere to multiyear monitoring and maintenance schedules directly associated with site specific road and infrastructure stabilization, drainage and debris removal, while and after high intensity fire events.

In general the increasing frequency of high severity fires causes detrimental long lasting impacts to our goal of providing safe and reliable transportation facilities. Realizing the compelling data regarding the effects of climate change and continued inconsistent and inefficient forest management, fire suppression and management techniques by the federal government agencies we have cause for great concern. The Karuk Tribe has acknowledged accessing additional funding with a focus on increased staffing, planning and heavy equipment procurement as a urgent priority to ensure safety while and after an emergency incident.

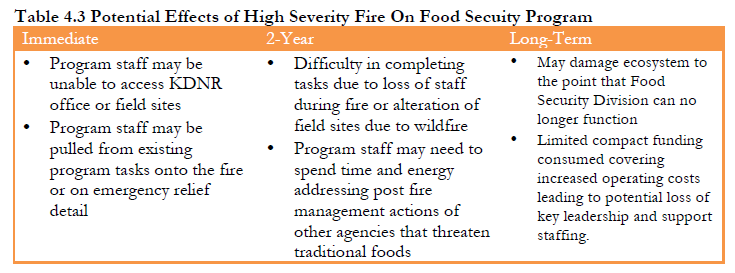

High Severity Fire and Vulnerabilities to Food Security Program

Traditional food, fiber and medicine are vitally important for Karuk people. Not only do they provide materials necessary for cultural continuity and the preservation of traditional knowledge, they also support physical and mental health. Cultivating, harvesting, processing, preserving and consuming Native food and medicine provide the framework for the Karuk socialization process and religious belief. Rooted first and foremost in this broader importance of traditional food, Karuk food security exists when people have the physical, social and economic access to enough safe and nutritious Native foods needed to maintain an active and healthy life.

This document takes a dual approach to food security. Access to healthy foods in general, including foods that may be purchased in stores or procured in home or local gardens, is also considered here. With one highway frequently closed due to slides, major accidents and wildfire, and the minimum distance to a comprehensive grocery store being roughly 94 miles from the heart of Karuk ancestral territory at Katimiin, the mid Klamath region is considered a food desert.

The potential for increased fire size and severity in the face of climate change creates vulnerabilities to food security across all three levels of our analysis: impacts to traditional foods, impacts to program infrastructure, and impacts to management authority. While cooler burns enhance growing conditions for nearly all Karuk traditional foods, high severity wildfire can negatively impact species of key cultural significance as well as those that make up the majority of the total calories and protein source in traditional diets – namely tan oak acorns and salmon.[1] Other species vital to food security include deer, huckleberries, tan oak mushrooms and elk. Negative impacts to these species have profound ramifications for nourishment and hunger, physical and emotional health, economic stability, social relations, cultural and ceremonial practice, and political status. Additionally, the Karuk Department of Natural Resources (KDNR) has a thriving Food Security Division which can be negatively impacted in light of high severity fire. The Karuk DNR Strategic Plan lists the goal of this program as achieving:

a sustainable food system that results in revitalized traditional ecological knowledge and practices, healthy communities, restored healthy ecosystem, and healthy economy grounded in traditional subsistence . . . Efforts include but are not limited to: measuring and monitoring designated plots in order to document the efficacy of land management techniques on the quantity and quality of food and fiber species; implementing and evaluating events and activities to inform the tribal community on traditional land and resource management, food and fiber harvest, preparation and storage; and improving agro-forestry management to increase supply of traditional foods.

High severity wildfire may affect the Food Security Division’s capacity in multiple ways. As with other vulnerabilities discussed in this report, we consider potential impacts across three time scales. During a high severity wildfire event, division staff may be pulled away from other responsibilities, may be unable to work due to lack of access to field sites and/or KDNR office location in Orleans if transportation, power supplies or phone service are impacted.

[1] See details of how cultural burning enhances these species as well as how high severity fire and the effects of other management impair particular species in the Species Profiles in Chapter Three

In the immediate aftermath of a high severity wildfire, division staff may be delinquent in meeting responsibilities and grant-funding deliverables if they have lost staff or time during the fire event. Additionally, staff may be called upon to spend time and energy engaging with post-fire management actions of the USFS or other agencies that cause further harm to traditional use species. “Fire season and its aftermath seriously impact our objectives’ effectiveness,” reports Karuk Food Security Division Coordinator Lisa Hillman. “Half the time, we’re asked to meet with agency representatives or respond to queries in regard to cultural species protection; the other half, we have to look over their shoulder to ensure that they actually do what we’ve requested. At the same time, we have neither the time to fulfill our own job responsibilities, nor is our time fiscally compensated. Who’s going to be there to protect cultural species when our project funding runs dry?”

As a result of the sheer commitment to their work, people do such tasks on top of their existing obligations. We have salaried staff working in excess of 60 hours a week, which equates to about $15.33 an hour for an employee working at a $47,840 salary rate. When you add the cost of using personal vehicle use on top of that without the time, energy or budget to file paperwork to charge mileage, and people are working because they care, not because they are advancing financially in life.

Karuk Water Quality Program

The Klamath River and its tributaries are essential for the cultural, spiritual, economic and physical health of Karuk people. Water quality is imperative for access to healthy foods, and necessary for multiple economic, social, spiritual and cultural activities to occur. Water quality TMDL standards are set in the context of Karuk subsistence and cultural uses. Water quality impacts matter for their impact on species of concern, and on human health from drinking as well as the human health consequences of consuming contaminated traditional foods.

The Karuk DNR Strategic Plan notes:

The Water Quality Program conducts monitoring and research along 130-miles of the Klamath River and tributaries. This includes data collection on temperature, dissolved oxygen, sediment, nutrients, phytoplankton, toxins, etc. This data informs state and federal processes and policies. Additionally, the Water Quality management level staff represent the concerns of the Karuk Tribe on Klamath Basin watershed management activities and promote sound water management practices that improve and restore water quality conditions. This program includes a Water Quality Coordinator, Program Project Coordinator and Technicians as needed. . . the Watershed Restoration Program also conducts cross-programmatic work that has a direct effect on improving water quality and quantity.

High severity fire affects the capacities of the Karuk Water Quality Program in a variety of ways. Program staff participate in regionally coordinated monitoring programs and collect samples for multiple agencies in the course of their duties. These activities require staff to collect samples at specific times and places throughout the watershed. Road delays and closures – a normal and frequent occurrence during wildfire events – can prevent arriving at sampling sites at the required time and thus have serious impacts on program functionality. Furthermore, once taken, samples must be sent out for processing in very specific and short time frames. Karuk Water Quality Biologist Susan Corum notes “If you work in 110 degrees for 8 hours you don’t want the data to be worthless because you missed the Fed Ex person.” Transportation delays and road closures can not only invalidate a day’s work, but impact the quality of entire data sets. Multiple gaps in seasonal data sets damage the overall quality of the program’s work and may affect funders or relationships with partners.

Because water quality staff work long hours in the field their respiratory and emotional health may be significantly impacted by smoke, which has both immediate and longer term impacts on program capacity through staff burn out and turn over. These impacts are multiplied when staff work all day in heavy smoke for multiple days in a row. Road closures and delays can make a 10 hour work day into a 14 hours, a situation which impacts morale as well as health. INSERT PHOTO.

Additional workload during fires may occur for water quality staff when there are spills of fire retardant in the river or lakes. The water quality program is not set up to monitor such events as grant funding is generally not available to conduct such work, nor is funding set aside from responsible agencies to address these eventualities.

During the months following high severity fires the water quality program faces continued impacts. As previously discussed, road closures as a result of sedimentation and flooding frequently occur up to several years following a high severity fire. Road closures from these events can impact daily field work as described above. Increased sedimentation is an important water quality problem, yet like the impacts from retardant drops, this is not one that the Tribe’s water quality program is set up to monitor. In the immediate aftermath of a high severity wildfire, division staff may be behind or delinquent in meeting responsibilities and grant-funding deliverables if they have lost staff or time during fire events. In the time period following fires, staff may be called upon to spend time and energy engaging with post-fire management actions of the USFS or other agencies that cause further harm to traditional use species. In 2016 the release of the Westsides salvage timber sale (following the 2014 July Complex Fire) requested emergency water quality exemptions from the Environmental Protection Agency.

Karuk Fisheries Program

Fisheries are vital for the food, health, culture and well being of Karuk people. Salmon are a staple in Karuk diet. The Karuk as the first peoples of the Klamath Mountains have been the managers of salmon since time immemorial. Our ceremonial practices and principles not only revolve around the life cycles of salmon and steelhead, they historically dictate the harvest seasons for all uses of salmon in the watershed. Contemporary harvest management regulations do not recognize this fact, and in many cases operate in under opposing principles and we have experienced significant decline in species abundance as a result. The Karuk DNR Strategic Plan lists the goal of this program as:

…garnering a greater understanding of ecological processes that support fisheries through research and monitoring, as well as enhancing fisheries habitat through restoration activities. Research and monitoring informs practices such as river flow and harvest management.

The Karuk Fisheries Department started with funds in the amount of $150,000 since this initial annual funding was received in the late 80’s, the fisheries department has leveraged those funds to establish a full-fledged Department of Natural Resources with a annual budget of over $2.5 million that exists primarily due to constantly shifting grant funded projects. The program currently employees between 7 and 15 people depending on the season.

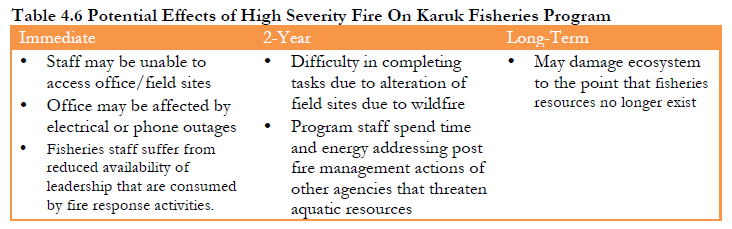

High severity wildfire may affect fisheries program capacity in multiple ways. As with other vulnerabilities discussed in this report, we consider potential impacts across three time scales. During a high severity wildfire event program staff may be pulled away from other responsibilities, may be unable to work due to lack access to workplace sites at the Department of Natural Resources office in Orleans or in the field if transportation, power supplies or phone service are impacted.

Karuk Watershed Restoration Program

Karuk ancestral territory contains hundreds of miles of unmaintained and poorly maintained logging roads that pose a threat to watershed processes, water quality, and aquatic habitats via sedimentation. The Karuk DNR Strategic Plan describes the purpose of the Watershed Restoration Division as “to protect the habitat of anadromous fish by decreasing the sedimentation caused by the road networks within watersheds of critical concern.”

The Watershed Restoration Program was established in 1999 with the purpose of identifying, planning and implementing projects including the repairing and upgrading or roads, road decommissioning and slope stabilization, restoration forestry, streambank stabilization, stream habitat protection and enhancement. The Watershed Restoration program works with the Fisheries Program to re-establish hydrologic connectivity, promote fish passage, and establish and maintain coldwater refugia in key Klamath and Salmon River tributaries. This program employs a Watershed Restoration Coordinator, Heavy Equipment Operators and Restoration Laborers as needed.

High severity fire affects the capacities of the Karuk Watershed Restoration Program in a variety of ways. During and immediately following fires restoration to remediate soil disturbance is needed and is a major component to the work of the Watershed Restoration Program. Because there are few qualified individuals in this rural community and programs are small, key individuals are often needed in multiple places at once, especially during the crisis climate generated during high severity fires. Tribal staff within this program may be pulled from immediate duties in order to participate as monitors on fires, or other tasks. Equipment is also often needed during fires. While equipment may be reimbursed on a per diem basis, reimbursement formulas do not adequately cover the actual costs of equipment wear and tear.

During the months following high severity fires the Watershed Restoration program faces continued duties in responding to road closures as a result of sedimentation and the flooding which frequently occur up to several years following a high severity fire, especially if large areas of hillsides are denuded. In the immediate time period following fires, staff may be called upon for their expertise to engage with post-fire management actions of the USFS or such as salvage logging that involve road building and pose risks for future sedimentation. Tasks which staff may desire to execute, but which there is often inadequate time or funding include soil mapping, vegetation correlation, and erosion and sediment control as a result of run-off from high-intensity fires. Soils are a major consideration in the NEPA process and constitute an important specialty area for management of forest road systems. These NEPA related planning tasks pose long-term challenges to program capacity that are potentially amongst the most significant faced by a DNR program. These NEPA related planning tasks have until recently been focused on response to other agency planning efforts instead of a reliably funded proactive approach like that currently being demonstrated by the tribally led Western Klamath Restoration Partnership.

Impacts to program capacity are interwoven with impacts to management authority. The Watershed Restoration Program’s goal is to protect watersheds that serve as habitat for Tribal trust species while maximizing the Tribe’s and local communities long-term economic and cultural benefits. Lack of knowledgeable traditional stewardship on behalf of the USFS and other agencies has created landscape conditions that have ignored and devastated traditional resources and now threatens the well being of both the forests and the forest based communities. Management policies of the current land managers have undermined traditional avenues of access to resources for this program. These existing conditions are exacerbated in the context of high severity fires given that much of the work of the watershed restoration program is in response to the past management actions of the Forest Service. For example, in the event of increased likelihood of high severity fires the Forest Service can be less willing to decommission roads given the perception they may be needed as future fire breaks.

Integrated Wildland Fire Management Program

The Karuk Integrated Wildland Fire Management Program began as the Fire and Fuels program in 1994 and has recently expanded to include restoration forestry activities and landscape level planning for future fires. The program has three full time staff positions and employs up to 30 people on fuels reduction projects.

A major goal of this program of direct relevance to this vulnerability assessment is the implementation of traditional fire management regimes. As noted throughout this document, forestlands within Karuk ancestral territory have been severely impacted by extractive timber production, single species management, road building, massive fuel loading, and fire suppression. One dimension of this program is to restore natural forest processes and historic forest composition that promote biological diversity and multi-aged ecosystems, with standing dead trees, downed trees, and logs present in riparian zones and streams. These actions can be achieved through management activities such as timber harvest and stand improvements (i.e. thinning), silvicultural treatments, riparian restoration, and prescribed and cultural burning and managed wildfire. The program does not currently have necessary the leadership or capacity to implement the restoration forestry goals relating to the wildland management and restoration forestry, thus more work day to day is carried out with regards to fuels reductions. The Karuk DNR Strategic Plan describes:

The Wildland Fire Program is principally concerned with protecting life, property, and cultural/natural resources from uncharacteristically intense wildland fires. It is the Tribe’s intention to achieve this by restoring traditional fire regimes on a landscape scale within Karuk ancestral homelands and implementing restorative forestry practices. An important element of this work is ensuring a well-trained, highly professional local fire and fuels management workforce. It also includes having a collaborative interagency body that can coordinate, communicate, and agree on management methods during wildland fire events, as well as preventive measures including the reintroduction of prescribed and cultural burning throughout Karuk ancestral homelands. This is a large part of the eco-cultural revitalization approach being instituted by DNR, as described in the ECRMP. Currently, this program staffs an Assistant Fire Management Officer/Fuels Planner and Fire and Fuels Operations Specialist, in addition to necessary Squad Bosses, Crew Bosses, and Crew Members, based on seasonal need as funding allows.

The Integrated Wildland Fire Management Program capacity is significant affected during, immediately after and in the longer-term aftermath of high severity fires. Indeed, the capacity of this program is likely the most affected of any DNR program.

During fire events themselves staffing levels, interagency coordination, and communication increase significantly. The Deputy Director of Eco-Cultural Revitalization is responsible for an untenable work and supervisory load and the program does not meet the necessary supervision requirements. On top of this workload, the task at hand is enormous with much at stake given that many of the vulnerabilities faced by specific cultural use species in light of increasing high severity fire discussed in Chapter Three occur in fact due to fire suppression actions. Decisions made by USFS and CALFIRE about what is to be protected and how to protect it including the use of back burning, the creation of fire lines and the use of chemicals and fire retardants have all created profound damage for the ecology of the region and for culturally important food species and gathering areas. Diversion of staff resources and time in conflict and consultation over these decisions exacerbate the abovementioned institutional vulnerabilities leaving fewer resources for progressing our actions in positive, proactive directions (e.g. directions that builds upon traditional ecological knowledge, preserves our living culture, and enables tribal members to serve a traditional role in a contemporary context). Fire fighting activities of high severity fires also hold the potential to interfere with the ability of Karuk tribal members to perform cultural practices and erode the Karuk Tribe’s sovereignty over tribal lands, resources and constitutional jurisdiction. Staff within this program sit at the interface, attempting to influence these outcomes.

Furthermore decisions made and actions taken during fire suppression set up cycles for future fire outcomes. Program staff and especially program leadership is at the interface between traditional Karuk understanding of fire, cultural consequences and the top down hierarchal fire fighting machine of CALFIRE

As if the above weren’t enough, leadership within the Integrated Wildland Fire Management Program has the near impossible job of attempting to protect critical tribal cultural resources under conditions of limited recognition of the Tribe’s management authority (see Chapter Five for detailed discussion). Staff in this position are under quite significant pressure. On top of this, frequent turnover in Forest Service and CALFIRE staff means that conversations, decisions happen again and again. These conditions create enormous fatigue. Deputy Director of Eco-Cultural Restoration and traditional practitioner Bill Tripp describes the devastating emotional impacts of trying to communicate Karuk perspective on fire and protect cultural resources in the face of Forest Service presence fighting the large fires of 2008.

On these fires, every two weeks you are dealing with new people, and you’re going over the same things, and you are trying to re-justify every decision that was made where you were barely able to hold onto protection of one little piece of something. And then you’re losing a piece of that cause new people came 14 days later. And then you’re losing another piece of that and another. And you spend your whole time going over everything that you just went over again, and again, and again. And losing a little bit every time. And it causes some serious mental anguish.

Beyond the fire events, infrastructure within this program is tapped in ways that are not sustainable long term. The Karuk DNR Strategic Plan describes how “use of the KCDC as fiscal agent and equipment provider (e.g. vehicles) for fire and fuels program, which creates unnecessary complexity, chain of command issues, slows fiscal processes, and causes other administrative concerns regarding separation of managerial and enterprise roles.”

In the bigger picture the Integrated Wildland Fire Management Program has visionary goals for the restoration of traditional fire regimes to Karuk ancestral lands. These goals are more vital than ever in light of climate change. However, erosion of program capacity is a significant barrier to implementation of this important vision. Program capacity regarding wildland management and restoration forestry is growing, but is slowed by the fact that program staff are frequently pulled onto fires. This situation keeps the Integrated Fire and Wildland Management Program in a more defensive short-term structure, slowing the long-term goal of implementing the traditional fire management regimes that are especially needed in light of climate change.

In the longer term, the Karuk DNR continues to pursue cooperative agreements with the U.S. Forest Service, BIA and other agencies/institutions to enhance restoration forestry activities within Karuk ancestral territory. For example the Tribe is a key leader in the Western Klamath Restoration Partnership (WKRP). This is an open group comprised of the Federal, Tribal, and Non-governmental Organization (NGO) participants with the inclusion of facilitators and additional invitees. This Partnership allows diverse stakeholders to come together to accomplish work by identifying Zones of Agreement where all parties agree upslope restoration needs to occur. The Somes Bar Integrated Fire Management Project utilizes WKRP developed strategies to restore fire process in the WUI after a century of fire exclusion. The Proposed Action consists of mechanically and/or manually treating, then introducing controlled fire on the landscape of 6,500 acres of National Forest System land for fuels reduction and forest health. Once fuelbreaks have been created by mechanical and/or manual treatments, prescribed fire will be introduced into this landscape at regular intervals by the Tribe and/or the US Forest Service using known practices and tribal knowledge to continue to improve and maintain the health of the Forest.

In addition to the Somes Bar project, planning has begun for two additional pilot projects in Happy Camp and Forks of Salmon aimed at reintroducing good fire on over 40,000 acres in the WUI. These projects demonstrate both how fire can be returned to the WUI after long periods of fire exclusion, and how in areas where several recent fires have burned, fire processes can be restored relatively quickly and easily to reduce future wildfire expenditures. The Tribe’s ability to take a leadership role in this process is key to success, yet managing a complex, multi-agency collaborative network is a complex and time consuming task for program staff. Furthermore, the increased frequency of high severity fires may affect the success of such proactive programs as a growing public fear of fire, increasing drought and other climatic factors increase the day-to-day challenges of cultural burning.

Health Program

The Karuk Tribal health Program provides service throughout the Karuk Service Territory- 150 miles along Klamath Corridor from Yreka to Bluff Creek with clinics three service areas (Happy Camp, Orleans and Yreka). The Karuk Tribal health program faces a number of challenges during high severity fires. In 2014 fires burning in the northern edge of Karuk ancestral territory had such hazardous air quality that it was unsafe for people to be outside for over a week. On five of these days, fine particle pollution exceeded local air quality meter measurability.

Fires can and do cause direct loss of life, as well as other injuries to which the health clinics respond. But more importantly, smoke from wildfires creates widespread and pervasive respiratory impacts to human health across the community to which clinic staff attempt to respond. Smoke from forest fires consists of carbon dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, ozone, particulate matter, hydrocarbons and other organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides, trace minerals and several thousand other compounds (Lipsett et al. 2008, p. 3). Of these it is actually the particular matter in smoke from forest fires that is often the most dangerous. In their report on smoke for the state of California Lipsett et al. (2008) note:

…fine particles are linked (alone or with other pollutants) with increased mortality and aggravation of pre-existing respiratory and cardiovascular disease. In addition, particles are respiratory irritants, and exposures to high concentrations of particulate matter can cause persistent cough, phlegm, wheezing and difficulty breathing. Particles can also affect healthy people, causing respiratory symptoms, transient reductions in lung function, and pulmonary inflammation. Particulate matter can also affect the body’s immune system and make it more difficult to remove inhaled foreign materials from the lung, such as pollen and bacteria. The principal public health threat from short-term exposures to smoke is considered to come from exposure to particulate matter (p. 4).

The report notes that exposure to smoke from forest fires leads to symptoms that “range from eye and respiratory tract irritation to more serious disorders, including reduced lung function, bronchitis, exacerbation of asthma, and premature death.” (p. 3). Respiratory impacts intersect with other health conditions and are especially significant for the elderly and young children. High severity large-scale fires burn for much longer than traditional cultural burning of the past, leading to particularly significant health impacts. As noted by staff in the Integrated Wildland Fire Management Program, “With fire exclusion we have a wider pendulum between fires and no fires, between smoke and no smoke, such that when fires occur there may be very large with heavy smoke for periods of weeks at a time. These circumstances tend to be particularly difficult for respiratory problems.” Indeed cultural burning is less impacting to human health than the high severity fires that result in its absence. In their work on pyrohealth, Johnston et al. (2016) note this contrast: “While no studies on smoke exposure from traditional indigenous landscape burning exist, the smaller mosaic of patch burning promotes small low intensity fires, which overall produce relatively lower emissions, due to the smaller spatial size and lower fuel loads under such fire regimes” (p. 3). Johnston et al. (2016) further write: “The cessation of indigenous burning, active fire suppression, introduced species, and a warming climate are all contributing to increasingly frequent, large-scale, intense fires in many flammable landscapes. Emissions from large landscape fires can be transported for long distances affecting large and small population centres far from the fires themselves. Smoke episodes from severe landscape fires result in measureable increases in individual symptoms and in population indices of ambulance call outs, admissions to hospital and mortality (p. 3).

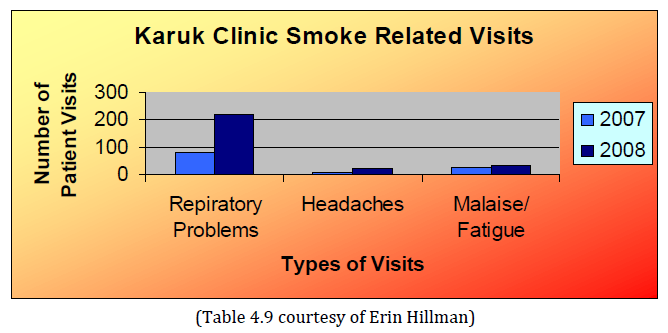

The increased frequency of high severity fire thus creates very serious potential impacts to the Karuk Health Program given that exposure to outdoor smoke from landscape fires is strongly associated with increasing respiratory symptoms which tend to occur during the fires, but also the deterioration of existing respiratory diseases, hospital admissions and deaths from respiratory causes which cause longer term impacts on not only the health program but of course the Tribal community. Information gathered in the 2007 and 2008 fires found significantly increased clinic visits to Tribal Clinics during these fires, see Table 4.9 below.

In addition to the higher patient load in clinics, the Tribe has stocked residential household size HEPA air purifier for distribution. Given that the Tribe no longer has a formalized department of emergency services, the health program attempts to fill the void in responding to these air quality dangers by distributing the air purifiers.

The Karuk Tribe participates in ongoing collaborations with Siskiyou County OES, including Preparedness Training and is a member of the steering committee for the Siskiyou County Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan. However, affected area residents are isolated and separated by great distances. All too frequently the Karuk Tribal Health Program attempts to respond to smoke hazards across ancestral territory ask with minimal available resources from outside agencies due to number of fires in the state.

In addition to more acute cases and the concerns of youth and elders who face particular vulnerabilities, thick smoke creates a general background hazardous working conditions for all people living in its vicinity. As Bill Tripp notes, “Poor air quality impacts are not limited to respiratory issues. Poor visibility suspends air support for fire fighting, but also suspends air transports to hospitals for emergency patients, a problem which we will likely face because of the character of the terrain that these fire fighters are working in.”

The Karuk DNR Strategic Plan notes “The Karuk DNR currently approaches minimizing the potential for long-term exposure from poor air quality related to wildlife fire by restoring traditional fire regimes to the point where seasonal ignitions would burn at relatively lower intensity and extent over time. The Tribe does not currently have dedicated air quality staff, however, there are research and development needs related to air quality monitoring, as well as education and outreach to the local communities regarding the science behind traditional fire management, policies, and practices as related to effects on air quality.”

References

Johnston, F. H., Melody, S., & Bowman, D. M. 2016. The pyrohealth transition: how combustion emissions have shaped health through human history. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, 371(1696), 20150173.

Lipsett, M., B. Materna, S. L. Stone, S. Therriault, R. Blaisdell, and J. Cook. 2008. Wildfire Smoke: A Guide for Public Health Officials http://www.arb.ca.gov/smp/progdev/pubeduc/wfgv8.pdf.

Petty AM, Bowman DMJS. 2007 A satellite analysis of contrasting fire patterns in Aboriginal-and European-managed lands in tropical north Australia. Fire Ecol. 3, 32–47.

Copyright © 2016 the Karuk Tribe. All rights reserved.

Unless otherwise indicated, all materials on these pages are copyrighted by the Karuk Tribe. All rights reserved. No part of these pages, either text or image may be used for any purpose other than personal use. Therefore, reproduction, modification, storage in a retrieval system or retransmission, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, for reasons other than personal use, is strictly prohibited without prior written permission.