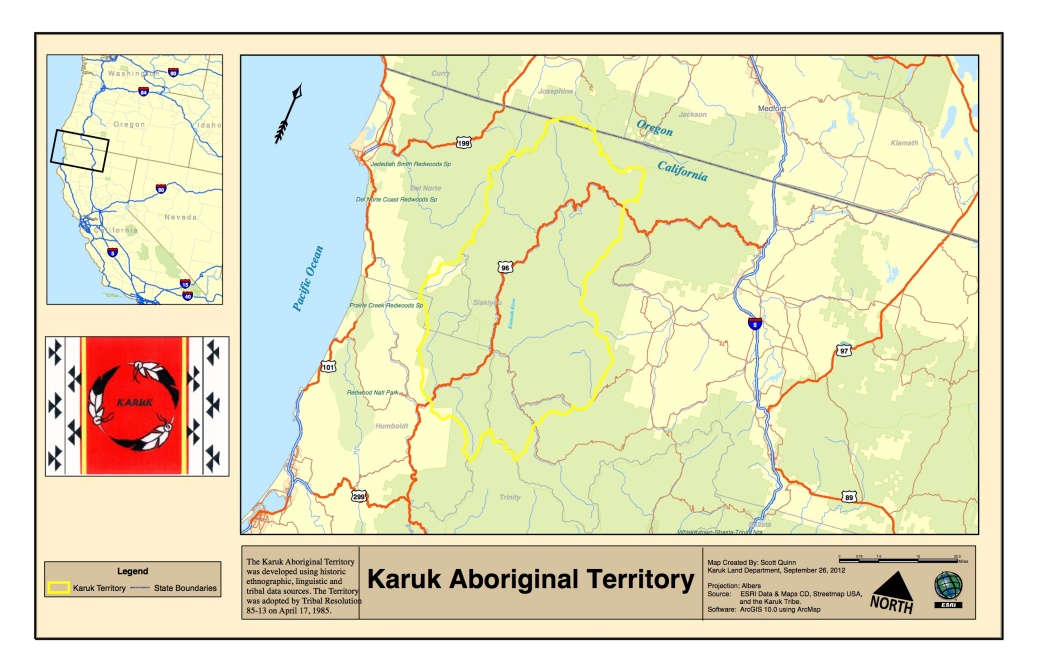

As a sovereign government, the Karuk Tribe claims jurisdiction over membership, lands and territory including the right to manage air, lands, waters and other resources as specified in the Karuk Constitution. This jurisdiction is recognized in Article II, Sections 4 and 5 of the Karuk Constitution which states: “The laws of the Karuk Tribe shall extend to:

4. All activities throughout and within Karuk Tribal Lands, or outside of Karuk Tribal Lands if the activities have caused an adverse impact to the political integrity, economic security, resources or health and welfare of the Tribe and its members; and

5. All lands, waters, natural resources, cultural resources, air space, minerals, fish, forests and other flora, wildlife, and other resources, and any interest therein, now or in the future, throughout and within the Tribe’s territory.”

The Karuk Tribe has developed programs, policies and departments to administer services to Karuk people and to uphold responsibilities to care for the land. Ultimately, tribal management authority emerges from Karuk occupancy and presence. This jurisdiction is based upon the fact that Karuk people have performed the practices of traditional management including fishing, hunting, tending, gathering, burning and more on their ancestral territory since time immemorial. Karuk people have never ceded title to these ancestral lands and retain reserved rights to continue the cultural and spiritual practices of caring for the land and species with whom they are related. Treaties signed in 1851 and 1852 were never ratified by the U.S. Congress, instead Karuk people have maintained a continued presence on the land conducting cultural and land management activities (Norton 2013, Risling 2013, Salter 2003). Karuk responsibilities to manage ancestral territory are referenced in the Karuk Creation Story as told here by Leaf Hillman:

“At the beginning of time, only the spirit people roamed the earth. At the time of the great transformation, some of these spirit people were transformed into trees, birds, animals, fishes, rocks, fire and air – the sun, the moon, the stars… And some of these Spirit People were transformed into human beings. From that day forward, Karuk People have continually recognized all of these spirit people as our relatives, our close relations. From this flows our responsibility to care for, cherish and honor this bond, and to always remember that this relationship is a reciprocal one: it is a sacred covenant. Our religion, our management practices, and our day-to-day subsistence activities are inseparable. They are interrelated and a part of us. We, Karuk, cannot be separated from this place, from the natural world or nature…we are a part of nature and nature is a part of us. We are closely related. “

Karuk management principles have been central to the evolution of the flora and fauna of the mid-Klamath ecosystem (Anderson 2005, Lake et al. 2010, Skinner et al. 2006). This ongoing environmental management is a manifestation of culture, relationships with the land, traditional knowledge, economic prosperity, spiritual practice and political sovereignty. Karuk tribal management authority is fundamental to self-determination, and is thus further supported by the Indian Self-Determination and Educational Assistance Act and multiple articles in the 2007 United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which the United States has endorsed as aspirational. The UNDRIP states that:

Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination (Article 3) . . . autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs (Article 4) . . . to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights (Article 18) . . . and States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them (Article 19) (United Nations 2008).

Article 29 section 1 further notes “Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources. States shall establish and implement assistance programmes for indigenous peoples for such conservation and protection, without discrimination”[1] (United Nations 2008). UNDRIP Articles 5, 18, 24, 25, and 31 also apply directly to Karuk traditional management authority in the face of climate change (see UNDRIP).

Article 29 section 1 further notes “Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources. States shall establish and implement assistance programmes for indigenous peoples for such conservation and protection, without discrimination”[1] (United Nations 2008). UNDRIP Articles 5, 18, 24, 25, and 31 also apply directly to Karuk traditional management authority in the face of climate change (see UNDRIP).

Other principles, statues and actions that underscore Karuk management authority include the Tribal Trust doctrine (Kronk Warner 2015, Tsosie 2003, Wood 2014), Executive Order 13175 regarding consultation with tribes, the 2009 Presidential Memorandum on Tribal Consultation, Secretarial Order 3206 American Indian Tribal Rights, Federal-Tribal Trust Responsibilities, and the Endangered Species Act, and Secretarial Order 3289 Addressing the Impacts of Climate Change on America’s Water, Land and Other Natural and Cultural Resources. Secretarial Order 3289 asserts that “climate change may disproportionately affect tribes and their lands because they are heavily dependent on their natural resources for economic and cultural identity,” emphasizes the primary trust responsibility of the Federal government to tribes, and affirms that “tribal values are critical to determining what is to be protected, why and how to protect the interests of their communities” (USDI 2009).

These and other principles underscoring tribal management authority are summarized in Tribal Climate Change Principles: Responding to Federal Policies and Actions to Address Climate Change (Gruenig et al. 2015) which underscores that “As sovereigns preexisting federal and state governments, tribes have government authority that they exercise over reservations, trust lands, and Tribal members who live within service-area jurisdictions that are not designated as trust lands” (p.4). Gruenig et al. (2015) also outline federal responsibilities towards tribes, stating“As recognized by the U. S. Supreme Court the United States has the highest moral obligation to act in the best interests of federally recognized Tribes” (p. 1). The principles outlined by Gruenig et al. (2015) have notably been adopted as part of resolutions developed by United States tribal organizations such as the National Congress of American Indians, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, and the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians.

In addition to statues and orders directly recognizing tribal authority, Presidential Executive Order 12898 requires federal agencies to achieve environmental justice by identifying and addressing the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of their actions on minorities and low-income populations and communities. This Executive Order also requires that agency decisions reflect an equitable distribution of related benefits and risks.

As this chapter will discuss, climate change in general and high severity wildfire in particular, creates vulnerabilities for Karuk tribal management authority. Here too the federal government explicitly acknowledges the application of the trust responsibility to protect lands from the impact of climate change affirming that, “the Department will ensure consistent and in-depth government to government consultation with tribes and Alaska Natives on the Department’s climate change initiatives” (Salazar 2009). Commitment to tribal engagement is explicitly noted in the President’s Climate Action Plan.

An emerging literature describes how tribes face a complex multitude of political threats in light of climate change (Cameron 2012, Donatuto and O’Neil 2010, Hanna 2007, Maldonado et al. 2013, Marino 2012, Stumpff 2009, Tsosie 2013, Whyte 2013, Williams and Hardison 2013, Wood 2014). Indeed, U.S. laws and policies are themselves increasingly exacerbating climate vulnerabilities for tribes. These political threats vary in part due to the wide variety of tribal political circumstances and compounded by new cross-jurisdictional complications that are overlaid in the face of climate change. In addition to differences concerning federal recognition and treaty status, climate change compels complicated cross-jurisdictional coordination between multiple agencies. These agencies exhibit a range of understanding of and commitment to their tribal trust responsibilities. Vinyeta and Lynn (2015) document the challenging and complex intergovernmental landscape faced by Pacific Northwest tribes when interacting with federal agencies in regards to the Northwest Forest Plan. A similarly, if not more complex intergovernmental context is bound to form part of climate change adaptation planning and implementation efforts, given that climate change is an all-encompassing challenge the impacts of which transcend single departmental or agency agendas.

Particular emphasis has been paid to the circumstances of treaty tribes, evaluating concerns such as how tribal harvest allocations and other important agreements assume stable ecological conditions (Goodman 2000), or the ways that coastal trust lands may be directly impacted due to sea level rise. For example, the Treaty Indian Tribes in Western Washington produced an important report in 2011 that concluded that the federal government is not fully implementing its treaty rights obligations (TITWW 2011).

Analysis of the broader impacts to tribal sovereignty and management authority, especially for tribes without treaties, is needed. To date little attention has been paid to how the particular climate stressor of increasing high severity wildfire may impact the political circumstances of tribes. We hope this chapter will be of use to tribes from a broad range of political backgrounds, especially those seeking to manage so-called off-reservation lands. We also hope that the focused attention given to high severity wildfire in particular will benefit both tribes and federal agencies seeking to uphold their tribal trust responsibilities.

Vulnerabilities to Karuk management authority in the context of high severity wildfire do not occur in a vacuum. These vulnerabilities must be understood in the context of the complicated existing cross-jurisdictional terrain in which Karuk management authority is often unacknowledged and misunderstood, and is compounded by the past, present and future actions of non-tribal land managers that jeopardize the ability of Karuk people and the Karuk Department of Natural Resources to sustain environmental management.

Agencies making decisions impacting Karuk Tribal Lands and resources include the EPA, USFWS, BIA, NRCS, USFS, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE), the State Water Board, and California Department of Fish and Wildlife. In particular, Karuk ancestral territory is located within the National Forest System. The Karuk Tribe maintains that it has never relinquished possession of these lands; the lack of recognized ownership or jurisdiction limits of the Tribe’s ability to care for traditional foods and cultural use species, as well as establish and maintain effective tribal programs. As noted in the Karuk DNR Strategic Plan, “Forestlands within Karuk ancestral homelands have been severely impacted by extractive timber production, single species management, road building, massive fuel loading, and fire suppression.”  Past management actions involving logging, road building and fire suppression interact with fire events to influence the Karuk Tribe’s present management authority, as do federal agencies’ management actions during, immediately after, and in the years following a fire. The next section outlines four general limitations to Karuk management authority in the face of climate change, and then details how these unfold in light of high severity fire at three scales: during fire events, and in the immediate and long term aftermaths of high severity fires.

Past management actions involving logging, road building and fire suppression interact with fire events to influence the Karuk Tribe’s present management authority, as do federal agencies’ management actions during, immediately after, and in the years following a fire. The next section outlines four general limitations to Karuk management authority in the face of climate change, and then details how these unfold in light of high severity fire at three scales: during fire events, and in the immediate and long term aftermaths of high severity fires.

Management Authority and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

As stated throughout this report, Karuk management authority is grounded in tribal occupancy and presence, including the longstanding practice of traditional management. Traditional management is in turn grounded in traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), including critical knowledge concerning the use of fire. Protections for TEK are part of the federal trust responsibility to tribes, are part of multiple government responsibilities to tribes in light of climate change (CTKW 2014), and are explicitly outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations 2008), which states in Article 24 section 1: “Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital medicinal plants, animals and minerals.” Additionally, Article 31 section 1 states:

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

The importance of utilizing TEK in relation to climate change is underscored by Secretarial Order 3289 which notes “The Department will support the use of the best available science, including traditional ecological knowledge, in formulating policy pertaining to climate change” (USDI 2009).

Ironically, the increasing severity of wildfire poses a direct threat to TEK itself by heightening fear of its application. Traditional ecological knowledge is a living practice that must be carried out on the landscape through continued application and use. When the Tribe is unable to carry out traditional management species and culture, both decline. Threats to Karuk management authority are therefore also threats to Karuk traditional ecological knowledge and cultural practices. The Phase III Western Regional Science-Based Risk Analysis Report developed as part of the National Wildland Fire Cohesive Management Strategy affirms that in the face of continued fire exclusion, Native American cultural identity and traditional ecological knowledge are both at risk (USDA 2012, p. 30). In 1995, fire management comprised approximately 16% of the USFS budget; In 2015, that percentage had reached an unprecedented 50% of the agency’s budget (USDA 2015). With these dramatic increases in Forest Service activity and budget directed towards fire suppression[2], the Cohesive Strategy has focused on how the prohibition of cultural burning constitutes both an ecological problem and spiritual violation. The exclusion of fire from the landscape creates a situation of denied access to traditional foods and spiritual practices, puts cultural identity at risk, and infringes upon political sovereignty (Lake 2007, Norgaard 2014a and 2014b and 2014c). Attention to the relationships between management authority, traditional ecological knowledge and the use of fire becomes even more important to understand now that the instance and frequency of high severity fire is increasing with climate change. Continued denial of cultural burning damages the ecological functions and diminishes the availability of and people’s access to cultural use species. Fire exclusion thus constitutes a direct violation of UNDRIP article 31 section 1 (United Nations 2008).  Similarly, because fire suppression as well as firefighting activities interfere with the ability of members of the Karuk Tribe to perform cultural practices, these activities hold the potential to erode the Karuk Tribe’s sovereignty over Tribal Lands and cultural resources. These relationships in the face of climate change are described in detail in the reports “Karuk Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Need for Knowledge Sovereignty: Social, Cultural and Economic Impacts of Denied Access to Traditional Management” (Norgaard 2014b) and “Retaining Knowledge Sovereignty: Expanding the Application of Tribal Traditional Knowledge on Forest Lands in the Face of Climate Change” (Norgaard 2014c).

Similarly, because fire suppression as well as firefighting activities interfere with the ability of members of the Karuk Tribe to perform cultural practices, these activities hold the potential to erode the Karuk Tribe’s sovereignty over Tribal Lands and cultural resources. These relationships in the face of climate change are described in detail in the reports “Karuk Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Need for Knowledge Sovereignty: Social, Cultural and Economic Impacts of Denied Access to Traditional Management” (Norgaard 2014b) and “Retaining Knowledge Sovereignty: Expanding the Application of Tribal Traditional Knowledge on Forest Lands in the Face of Climate Change” (Norgaard 2014c).

Tribal Capacity, Funding Structure and Management Authority

“To respond to the impacts of climate change, Indigenous Peoples must have access to the financial and technical resources that are required to assess the impacts of climate change on their cultures, air, land and water, economies, community health, and ways of life, and address those impacts through adaptation and mitigation.”

– Tribal Climate Change Principles (Gruenig et al. 2015).

An abundance of environmental and climate justice literature emphasizes that poor people, people of color, women, and Native Americans are and will continue to be more vulnerable in the face of climate change (Bennett et al. 2014, Cuomo 2011, Lynn et al. 2011, Maldonado et al. 2013, Shonkoff et al. 2011, Vinyeta et al. 2015). For tribes, these impacts from climate change come not only from the relatively intact relationships tribal communities may have with impacted ecological systems, but from the unequal financial and infrastructural capacities of tribal governments to respond vis-à-vis other entities. A central corroborating aspect of this problem is that Karuk management authority is not recognized or even understood. The Karuk Tribe faces challenges not only in terms of total funding available for climate related work, but in the structure of that funding in the form of grants. Grants are tied to specific projects with deliverables attached and staff hours that must be accounted for, as opposed to the broader flexibility from operating on BIA base funds. These capacity-related challenges, discussed in detail in Chapter Four, translate into vulnerabilities in relation to management authority especially when jurisdiction is not acknowledged or when the emergency crisis mode of fires cause existing tribal authorities to be over-ruled or ignored as will be discussed here. When federal decisions and actions compromise tribal lands and rights, time and resources that tribal staff could have invested into the advancement of tribally-led initiatives that build upon traditional ecological knowledge, preserve living culture, and nurture traditional roles, is suddenly diverted towards long, complex, intergovernmental conflict resolution and consultation processes, exacerbating the abovementioned institutional vulnerabilities faced by tribes. Tribal capacity is needed more than ever to assert sovereignty and management authority in the context of climate change, yet climate change itself holds the potential to undermine that very capacity and with it the ability of the Karuk Tribe to assert management authority.

New and Rapidly Shifting Jurisdictional Terrain

Climate change is also rapidly reshaping the legal landscape as changing ecological conditions and political dynamics are generating numerous planning efforts, judicial rulings, policies, and collaborative configurations of state and federal actors (Bronen 2011, Burkett 2011, Kronk Warner 2015, Mawdsley et al. 2009, Ruhl 2009). These collaborations and measures are necessary responses in the face of circumstances that clearly exceed prior jurisdictional boundaries. Yet, in part because there are still very few comprehensive federal laws applying to either the adaptation or mitigation of climate change, regional, state, and local efforts have emerged ad hoc. In the absence of an overarching legal framework at the federal level, tribes face potential loss of acknowledgement of their jurisdiction if they are excluded from or cannot keep up with the multiple and rapidly changing dynamics between federal and local actors.[3] Awareness and emphasis on federal tribal trust responsibilities – frequently overlooked in the best of times – are further lost in the midst of this new rapidly shifting policy terrain where the sense of crisis may be further impetus for their negation. The Tribal Climate Change Principles reports:

“Over the last several years, more than fifteen climate change committees and working groups have been formed within and among federal agencies. Many of these did not or do not include Tribal representation. Simultaneously, many of the committees that did or do include Tribal representatives only had or have nominal representation” (Gruenig et al. 2015, p. 5).

Multiple examples of regulations and planning efforts developed in light of climate change that failed to uphold federal tribal trust responsibilities and/or adequately engage the Karuk Tribe have emerged just in the short time frame of this climate vulnerability assessment. For example, the EPA rules for ground level ozone developed during 2015-2016 challenge both Karuk program capacity and management authority. Ground level ozone, which poses a hazard to human health, is increasing with warmer air temperatures resulting from the changing climate (Luber et al. 2014). Ground level ozone is also produced during forest fires, and the new EPA rule applies to prescribed burns as part of the federal response to health-related dimensions of climate change. There is, however, no exemption for cultural burning which is instead treated as an anthropogenic pollutant alongside vehicle emissions. In essence cultural burning is treated as part of the problem rather than a path to a potential form of climate mitigation. This regulation thus becomes yet another constraint undermining the Karuk Tribe’s efforts to apply prescribed fire and restore cultural burning at a landscape scale.

Multiple examples of regulations and planning efforts developed in light of climate change that failed to uphold federal tribal trust responsibilities and/or adequately engage the Karuk Tribe have emerged just in the short time frame of this climate vulnerability assessment. For example, the EPA rules for ground level ozone developed during 2015-2016 challenge both Karuk program capacity and management authority. Ground level ozone, which poses a hazard to human health, is increasing with warmer air temperatures resulting from the changing climate (Luber et al. 2014). Ground level ozone is also produced during forest fires, and the new EPA rule applies to prescribed burns as part of the federal response to health-related dimensions of climate change. There is, however, no exemption for cultural burning which is instead treated as an anthropogenic pollutant alongside vehicle emissions. In essence cultural burning is treated as part of the problem rather than a path to a potential form of climate mitigation. This regulation thus becomes yet another constraint undermining the Karuk Tribe’s efforts to apply prescribed fire and restore cultural burning at a landscape scale.

By contrast, the 2005 Western Regional Air Partnership Joint Forum on Fire Emissions[4] relates to Tribal Authority under the Clean Air Act. This document contains guidance on categorizing natural vs. anthropogenic emissions sources, and identifies a process for classifying tribal cultural burns as a natural emissions source along with wildfires (prescribed fire is an anthropogenic source). The categorization of tribal cultural burns for maintenance purposes as natural would mean that tribes do not need to obtain permits or to conduct planning to carry out cultural burns, thereby alleviating the costly and bureaucratic barriers. By contrast, recognition of the longstanding use of fire to shape the landscape approach is not reflected in the new EPA ozone rule. Bill Tripp noted this circumstance on a call with the EPA, “Our situation [longstanding proactive use of fire as management tool] is not reflected in this process.” He was informed that although the final rule was out, there would be additional opportunities for comment. But as Bill Tripp asserts, “we don’t have the capacity to respond. Federal agencies are responsible for making sure that tribal consultation takes place, but this has not occurred. Tribal consultation cannot occur effectively in part because the Karuk Tribe does not have capacity to engage.” Thus, in the face of federal assumptions about what is part of the “natural” background condition (climate induced wildfire but not cultural burning), rules that fail to fit the complexity of the Tribe’s political and jurisdictional experiences, rules written by one agency and implemented by another, and tribal staff and budgetary shortages that limit tribal capacity, the system is so unfavorable for effective and positive tribal engagement that Bill Tripp commented that “it is better not to consult because then you have to come into compliance.”

A second example comes from climate planning efforts developed by the U.S. Forest Service. As of 2016, the U.S. Forest Service is engaged in planning efforts within Karuk ancestral territory and homelands through revisions to the Northwest Forest Plan and eventual revisions to the Forest Plans on the Six Rivers and Klamath National Forests. Climate  planning is relevant for both efforts, but explicitly considered in the revisions for the Northwest Forest Plan. Executive Order 13175 and other statues referenced earlier in this chapter affirm the obligation of federal agencies to protect tribal resources, tribal rights to self-governance, and engage in government-to-government consultation on issues that will impact tribal rights and resources, and to ensure that tribal resources are protected in the face of climate change. It is particularly important that federal climate adaptation planning engage tribes not only due to the unique tribal needs and perspectives, but because the regulations themselves can and do negatively impact tribes.

planning is relevant for both efforts, but explicitly considered in the revisions for the Northwest Forest Plan. Executive Order 13175 and other statues referenced earlier in this chapter affirm the obligation of federal agencies to protect tribal resources, tribal rights to self-governance, and engage in government-to-government consultation on issues that will impact tribal rights and resources, and to ensure that tribal resources are protected in the face of climate change. It is particularly important that federal climate adaptation planning engage tribes not only due to the unique tribal needs and perspectives, but because the regulations themselves can and do negatively impact tribes.

In 2015, and as part of the above-mentioned efforts, the U.S. Forest Service hired a consulting firm known as EcoAdapt to conduct a climate vulnerability assessment for multiple forests across Northern California including the Six Rivers and Klamath National Forests that are situated within Karuk ancestral territory. Neither EcoAdapt nor the U.S. Forest Service initiated government-to-government consultation with the Karuk Tribe. Instead, members of the Karuk and other regional tribes were contacted in the same manner as stakeholders, and treated as such in the process (TRT 2016). As a result of the lack of consultation, Karuk tribal staff and consultants had to invest valuable time and resources to bring this problem to the attention of both the Forest Service and EcoAdapt, and to call for a legitimate government-to-government consultation process. Considerable time was also required on the part of Forest Service staff and consultants. Ultimately, the U.S. Forest Service’s failure to engage the Tribe as a sovereign entity led to an inefficient process for all involved.

The National Climate Assessment and the Secretary of the Interior have made strong statements concerning the increased vulnerabilities tribes face in light of climate change. There is also an increasing emphasis on the need for collaboration and consultation across tribal and non-tribal jurisdictions. However, attention to tribal needs and tribal trust responsibilities is often lost in this rapidly shifting policy terrain. For example, when the Council on Environmental Quality released their final guidance on considering greenhouse gas emissions and the effects of climate change in NEPA reviews in August of 2016, the document contained no mention of the words Native, tribes, indigenous or consultation.

The exclusion of tribal trust responsibilities, tribal needs and perspectives within these ongoing climate processes represents more than just a legal or moral failure; it creates enormous inefficiencies and ultimately jeopardizes possibilities for successful outcomes. The Tribal Climate Change Principles notes the expertise and leadership that tribes bring to the table concerning climate change:

“The exclusion of tribes is detrimental to the federal government for several reasons. First, tribes are established experts in resiliency and adaptation given their long record of adapting to various historical stressors – genocide, removal, climatic events, etc. Next, as separate sovereigns, tribes possess the capacity to enact their own tribal laws. As a result, multiple tribes across the country are already using their tribal laws to innovate in the field of climate change adaptation. There are valuable lessons that the federal government can learn from these innovative tribal “laboratories” (Gruenig et al. 2015, p.6).

Crisis Management and Emergency Exemptions

Climate change is widely perceived to be an unprecedented circumstance — the largest crisis humans have faced. Urgent action is needed to promote ecosystem-wide changes, positive feedback loops, and the necessity for direct response lest conditions decline further. Certainly climate change compels immediate and large-scale response. Yet this sense of crisis and emergency – especially on behalf of non-Native agencies – underscores a range of emergency actions that further undermine Karuk management authority. Numerous policies set in place regarding tribal trust responsibility, tribal consultation, tribal needs and the importance of unique tribal perspectives are inadequately carried out on the ground. The federal-tribal relationship must be carried out effectively to ensure that tribes have the capacity to address the impacts of climate change on lands, natural resources, and uses both on and off-reservation. Under conditions of crisis management, such measures are even less likely to be engaged.

Focus and Interest of non-Native Researchers in Klamath Basin

Karuk ancestral territory is part of the Klamath-Siskiyou bioregion that has long been considered ecologically important for its rich species diversity and endemism (Briles et al. 2011, Sawyer 2007a and Sawyer 2007b, Whittaker 1961). While the region is at risk for increasing high severity fire, it also represents an area of California and the Pacific Northwest with relatively high biological, geological, and topographic diversity on the one hand, and less urban development on the other. In light of these factors the region is again being considered an important potential climate refugia, where species may be able to move northward or into higher elevations in the coming centuries. Indeed, the high levels of biological diversity occur in part because the region has been a refuge in past climate change events – a place conducive to the persistence of species vulnerable to climate change to which migration has occurred (Olson et al. 2012). This situation is an enormous ecological benefit, yet it too can pose challenges for Karuk tribal management authority, as scientists from outside the Klamath Basin take an interest in the region in light of the challenges faced by species across the West. These scientists who, with the right knowledge and under the right conditions, could develop mutually beneficial, collaborative relationships with the Tribe, might also undermine tribal authority by lacking awareness of tribal presence, knowledge, cultural practices, and the federal trust responsibility. This lack of awareness results in part from a long historical tendency, dating back centuries and implicit in the colonial discourse of manifest destiny, in which the presence, importance, and continuity of Native American tribes has been minimized or erased by Euro-American institutions, in an effort to legitimate the prior and ongoing abuses towards indigenous communities.

Tribal presence, needs and management authority are frequently overlooked even by those closer to home. Several climate vulnerability assessments have been conducted focusing on Karuk ancestral territory with little mention of the Tribe’s presence, much less acknowledgement of the role of humans in shaping ecosystem processes, understanding of ongoing tribal management desires, or the opportunities emergent from continued existence of Karuk traditional ecological knowledge (see 2nd Nature 2013, Barr et al. 2010, Cook et al. 2014, GHD et al. 2014). A review of articles on the importance of the Klamath-Siskiyou region as a climate refugia follows this same pattern. Such omissions represent modern-day examples of disregard for, and erasure of a Tribe that is very much present and vital to the region. This is particularly unfortunate given that much could be (and has been!) gained from collaborative processes in which the Tribe is acknowledged and incorporated as a sovereign partner with vast knowledge, stewardship experience, and management authority.

Taken together, the above factors of capacities and funding structure, new and rapidly shifting jurisdictional terrain, crisis management and emergency exceptions, and the focus and interest of non-native researchers in the Klamath Basin represent potential threats to Karuk management authority that emerge in the face of the increasing frequency of high severity fire that will be discussed next.

Vulnerabilities to Karuk Management Authority With Increasing Fire Severity

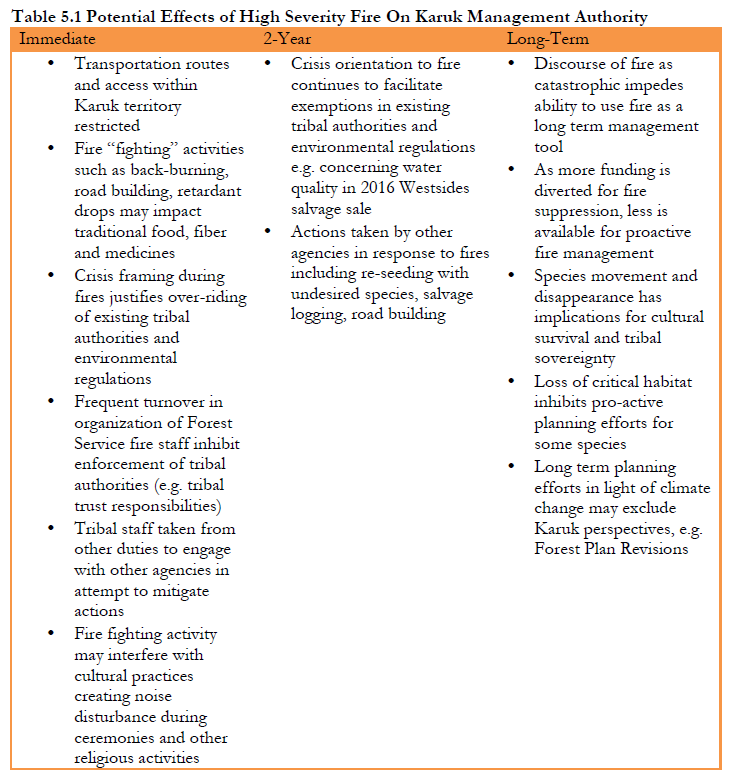

This next section considers the vulnerabilities to Karuk management authority that arise in the context of increasing size and frequency of high severity fires. Following the format used throughout this assessment, these vulnerabilities are examined at three temporal scales: those occurring during high severity fire events, those occurring in the immediate (roughly two year) aftermath of such fires, and, last, how increasing incidence of high severity fires negatively affects management authority over time. Table 5.1 summarizes vulnerabilities discussed here.

Karuk Management Authority During High Severity Fire Events

Just as the general forest management policy of fire suppression emerged from a non-Native value orientation focused on commercial timber, activities carried out in response to high severity fires reflect the economic, political and cultural values of the dominant non-Native world. During high severity fire events, firefighting activities interfere with the ability of Karuk people to perform their cultural practices, potentially eroding the Karuk Tribe’s sovereignty over Tribal Lands and cultural resources. Coupled with fear of fires, general public ignorance of Karuk traditional management processes related to fire further negatively affects the Karuk Tribe’s management authority during fires themselves. Non-tribal decisions regarding what is to be protected and how, and the fire management activities that follow— such as back-burning, road building, and retardant drops— rarely support tribal values or perspectives and in fact often profoundly damage culturally important food species and gathering areas.

When high severity fires occur, large numbers of firefighters with little knowledge of Karuk presence — much less the federal tribal trust responsibility — descend upon the area. Noise and intrusion from the use of helicopters when ceremonies are underway and the use of “federal closures” that denies people access to public lands are a de facto form of martial law, especially when armed officers enforce closures by arresting people for trespassing on their own public lands. Transportation within ancestral homelands and access to its cultural resources may be restricted. Fire lines and roads may be placed through culturally important areas, vital tree species such as tanoak or black oak may be intentionally cut down or severely burned as fire breaks, and snags that are important habitat for other cultural use species, including Pacific fisher, are likely to be cut as a pre-emptive tactic (Lake, pers. comm.). Actions such as falling trees, or use of heavy equipment or road building that are not normally allowed in riparian or wilderness areas will be given emergency exemptions during a fire. Cultural Vegetation Characteristics remnant of past traditional fire management practices of the Karuk people are bulldozed or burned in a manner uncharacteristic of the intended use. For example; ridge systems with a significant beargrass component are typically bulldozed to create a fireline, when in a cultural management scenario they would be frequently burned in a manner that the vegetation type itself would serve as a natural fuel break (B Tripp, pers. comm.). Revitalization of this frequent fire management practice would lessen the workforce needed over time, and would virtually eliminate the need to call in additional people and equipment during wildland fire events in these areas.

Fear of fire coupled with ignorance regarding tribal responsibilities support a crisis mentality in which emergency actions are taken without considering the long-term implications these actions may have for the Tribe or the ecosystem. The command and control organization of the Forest Service fire response, together with frequent personnel turnover, also limits the ability of Karuk tribal staff to communicate and influence management decisions. Karuk Eco-Cultural Restoration Specialist and traditional practitioner Bill Tripp describes the devastating emotional impacts of trying to communicate Karuk perspectives on fire and to protect cultural resources in the face of Forest Service presence fighting the large fires of 2008.

Fear of fire coupled with ignorance regarding tribal responsibilities support a crisis mentality in which emergency actions are taken without considering the long-term implications these actions may have for the Tribe or the ecosystem. The command and control organization of the Forest Service fire response, together with frequent personnel turnover, also limits the ability of Karuk tribal staff to communicate and influence management decisions. Karuk Eco-Cultural Restoration Specialist and traditional practitioner Bill Tripp describes the devastating emotional impacts of trying to communicate Karuk perspectives on fire and to protect cultural resources in the face of Forest Service presence fighting the large fires of 2008.

“In my situation I find myself quite a few times just to the point of asking why am I even here trying to do this? I should just go and be happy somewhere. On these fires, every two weeks you are dealing with new people, and you’re going over the same things, and you are trying to re-justify every decision that was made where you were barely able to hold onto protection of one little piece of something. And then you’re losing a piece of that because new people came 14 days later. And then you’re losing another piece of that and another. And you spend your whole time going over everything that you just went over again, and again, and again. And losing a little bit every time. And it causes some serious mental anguish.”

The use of fire retardants is another issue that directly impacts tribal people and species of importance given that a high percentage of tribal members get their food and water directly from the forest. Use of chemical retardants occurs without awareness or regard for this circumstance, and the Karuk Tribe has little to no ability to assert tribal authority regarding the use of retardants. Criteria for retardant use are set without regard for human occupancy, there is no long term monitoring or consideration of cumulative effects on water supplies, and recordkeeping for locations of retardant drops is haphazard at best (e.g. gps is not used to identify locations). Even when retardant drops have occurred into the river or other water bodies, tribal staff have been prevented from accessing the site to gather follow up water samples (S. Corum pers. Comm.). One Karuk elder, Marge Houston described how the Forest Service dropped fire retardant onto her prime acorn and mushroom gathering area, a site that was just 100-200 feet from her home:

“This summer that there was a less than an acre fire here on the Indian allotment and what happened was the Forest Service came in after it was under control they come in and did a Borate drop, or some fire retardant. They wanted to come down and do another one til we had to get out there and start screaming at them. And basically they said, “Well, we’ll only do two drops.” But you know there’s some big issues there. Because first of all that fire was under control. Second, it was less than an acre of fire. And now we have a contaminated subsistence harvest area along with other culturally sensitive areas¼They cut down my acorn trees. And they missed the fire to begin with¼. Sprayed it everywhere but on the fire. I couldn’t even breathe for three days. All the oyster mushrooms that I got up here on this [fire] I cannot eat. ‘Cause they come up and they’re pink. Just like the chemical that they sprayed. I can’t eat that. I’m not going to be able to eat a mushroom off that tree again. Damn.”

Present day threats to management authority during fire events intersect with past management actions of other agencies. Dr. Frank Lake has described how historic trails along ridges are places where fire had been used frequently to keep open travel routes and access gathering sites. Ironically in the early days of fire suppression, these ridges and trails were the most easily accessed and became the focus of fire suppression activities, in turn causing particularly large fuel build up over time. Now during fire events these same ridges and trails are often used for fire lines, meaning that sections will be “blackened” – a practice that causes direct mortality even to fire resistant cultural use species, and sterilizes the soil. As a result of this combination of past fire suppression and the creation of fire lines, culturally significant trails and ridges have some of the highest degree of imposed alteration of their historic cultural fire regimes.

Karuk Management Authority in the Immediate Aftermath of Fires

High severity fires impact the mid Klamath ecosystem in the immediate aftermath (roughly two years) in a number of ways. Karuk management authority is often challenged by non-tribal management actions such as re-seeding and re-planting, sediment control, road building, and salvage logging that occur when a state of “emergency” takes precedence over adequate government-to-government consultation. Re-seeding and re-planting activities can modify the make-up of the forest, create conditions that compromise culturally critical trees and herbs, and sometimes introduce genetically modified specimens that are not in accordance with tribal values. Areas developed as fire breaks are often used as roads, which affects Karuk management authority by further enabling commercial resource extraction. Salvage logging undermines Karuk management authority by removing woody forest material that is vital to various species of cultural importance. In the past ten years, the two National Forests occupying Karuk ancestral territory have proposed timber sales in order to ‘salvage’ trees burned during high severity fire. This trend is consistent throughout the Pacific Northwest; the majority of timber sales now take the form of salvage logging operations. In 2016 the Westsides salvage timber sale (following the 2014 July Complex Fire) proceeded with emergency water quality exemptions from the Environmental Protection Agency despite opposition from the Tribe.

Long Term Effects of Fire on Karuk Management Authority

In the longer-term aftermath of high severity fires, impacts to tribal management authority continue via both direct and indirect changes in the landscape. Species movement and disappearance have implications for cultural survival and tribal sovereignty, and long term planning in response to high severity fire may continue to limit Karuk traditional management. Over the long run, the continued crisis orientation to fire may shape management decisions, precipitate exemptions in existing regulations on logging and other post fire management activities, and inhibit the ability of the Tribe to conduct cultural burning in fire footprints. And, as more funding is earmarked for fire suppression, less is available for proactive fire management such as prescribed burns that can be carried out safely at appropriate times of the year.

Given that Karuk management authority is tied to traditional ecological knowledge as a living practice, the radical alteration of the land has potentially dire political consequences as Karuk Cultural Biologist and dipnet fisherman Ron Reed explains in this passage from Chapter Two:

“. . . the traditional foods that we need for a sustainable lifestyle become unavailable after a certain point. So what that does to the tribal community, the reason we are going back to that landscape is no longer there. So the spiritual connection to the landscape is altered significantly. When there is no food, when there is no food for regalia species, that we depend upon for food and fiber, when they aren’t around because there is no food for them, then there is no reason to go there. When we don’t go back to places that we are used to, accustomed to, part of our lifestyle is curtailed dramatically. So you have health consequences. Your mental aspect of life is severed from the spiritual relationship with the earth, with the Great Creator. So we’re not getting the nutrition that we need, we’re not getting the exercise that we need, and we’re not replenishing the spiritual balance that creates harmony and diversity throughout the landscape.”

Over the long run, repeated high severity fire holds the potential to reset much of Karuk ancestral territory to an early seral condition that has a tendency to burn at high severity over and over again. The process for such conversions varies by forest type, but essentially can occur if very severe fires occur in rapid succession before canopy cover can develop. At that point, the stand is unable to develop a fire resistant stand structure and will remain as fire-prone brush field. Future forest climate scenarios indicate that once high severity fire occurs, conifers in particular may not be able to reproduce in that area. Along with this potential is the loss of species that may cause a domino effect through the entire ecosystem. Such landscape alteration may be exacerbated by post-fire management actions of the Forest Service, including re-seeding burned areas with commercially valuable but fire-prone conifer species to create plantations for future harvest.

The increased instances of high severity fire will shape the long-term forest planning process. Of immediate importance in this regard is the role that climate change in general and increasing high severity fires in particular will play in shaping the Forest Plan revisions process for both Six Rivers and Klamath National Forests. As mentioned earlier, critical climate research relevant to forest planning has already been proceeding in the Klamath Basin in the absence of tribal consultation. It is essential that climate adaptation planning by the Forest Service and other federal agencies centrally involve tribes, as these policies directly affect resources of importance to the Karuk Tribe and, as it stands, the planning process currently ignores tribal management authority. Diversion of staff resources and time in the face of these conflicts leaves fewer resources for advancing the positive, proactive directions that are especially needed in light of climate change.

Conclusion

Traditionally, Karuk and other Tribes in the Klamath Basin use fire to manage the landscape.  Our traditional management practices prevent the build-up of fuels that could lead to severe fire events as well as manage for healthy stands of acorn bearing oaks, forage for large ungulates, and for other foods, fibers, and medicinal plants. Due in part to thousands of years of purposeful fire management, the forests of this region have benefited ecologically from fires that are low in heat production, or “cooler” fires. Paradoxically, large scale impacts from climate change are exempt from regulation, while the potential solutions in the form of traditional management have imposed regulatory barriers (Wiedinmyer and Hurteau 2010). Restoring balance in the fire regime and managing landscapes with time-tested traditional ecological knowledge is a priority in Karuk country, particularly as climate change impacts begin to intersect with the effects of decades of non-tribal land management. Now that there is collaboration on the Six Rivers National Forest, their Forest Plan may be revised. The development of this Vulnerability Assessment is the first step towards a Climate Adaptation Plan that can then be integrated into the new Forest Plan revisions. The Federal Lands Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLMPA) states in Sec. 202. [43 U.S.C. 1712] (b); “In the development and revision of land use plans, the Secretary of Agriculture shall coordinate land use plans for lands in the National Forest System with the land use planning and management programs of and for Indian tribes by, among other things, considering the policies of approval tribal land resource management programs.”

Our traditional management practices prevent the build-up of fuels that could lead to severe fire events as well as manage for healthy stands of acorn bearing oaks, forage for large ungulates, and for other foods, fibers, and medicinal plants. Due in part to thousands of years of purposeful fire management, the forests of this region have benefited ecologically from fires that are low in heat production, or “cooler” fires. Paradoxically, large scale impacts from climate change are exempt from regulation, while the potential solutions in the form of traditional management have imposed regulatory barriers (Wiedinmyer and Hurteau 2010). Restoring balance in the fire regime and managing landscapes with time-tested traditional ecological knowledge is a priority in Karuk country, particularly as climate change impacts begin to intersect with the effects of decades of non-tribal land management. Now that there is collaboration on the Six Rivers National Forest, their Forest Plan may be revised. The development of this Vulnerability Assessment is the first step towards a Climate Adaptation Plan that can then be integrated into the new Forest Plan revisions. The Federal Lands Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLMPA) states in Sec. 202. [43 U.S.C. 1712] (b); “In the development and revision of land use plans, the Secretary of Agriculture shall coordinate land use plans for lands in the National Forest System with the land use planning and management programs of and for Indian tribes by, among other things, considering the policies of approval tribal land resource management programs.”

Climate change is happening on such a large scale that it can appear to be a natural force, even as we know it to be anthropogenic. Climate change results from the emissions and build up of carbon dioxide and other climate gasses in the atmosphere. These emissions are in turn the result of political and economic systems organized around fossil fuel combustion. Ultimately, climate change is the product of unsustainable Western land management practices and the rise of political and economic systems for which indigenous people hold little to no responsibility.

In this context, the crisis posed by climate change is also a strategic opportunity not only for tribes to retain cultural practices and return traditional management practices to the landscape, but for all land managers to remedy inappropriate ecological actions, and for enhanced and successful collaboration in the face of collective survival. Recent recognition of the validity of traditional ecological knowledge coupled with the recognition of the need for collaboration in the face of high severity wildfire (e.g. FLAME Act of 2009, Western Regional Strategy Committee 2012), and recognition of the failures of existing Western scientific perspectives and existing management approaches including the focus on single commodities and single species management, have combined to create an exciting political moment in which tribes are uniquely positioned to lead the way. In the mid-Klamath region specifically, many goals in the Forest Service’s own management plan can be best achieved through restoring Karuk tribal management.

“As political sovereigns, Tribes are able to practice stewardship and apply traditions, practices, and accumulated wisdom to care for their resources, exercise co-management authorities within their traditional territories, and strongly influence and persuade other political sovereigns to protect natural resources under the public trust doctrine. As signatories to treaties, some Tribes are able to call upon the obligations of the United States to protect their reserved rights to fish, hunt, trap, and gather on FS lands. Tribes that do not have ratified treaties still retain reserved rights. Both treaty and non-treaty Tribes seek to manage off-reservation lands.”

— Intertribal Timber Council, 2013, p.15

This need for a new and active landscape management strategy has specifically been initiated in the context of both wildfires and climate change. As indicated by the Intertribal Timber Council (2013), “Tribal, FS, BIA land managers recognize the importance of active landscape management to reduce the need for and cost of fire suppression. Treating the cause of the problem (overstocking, excessive fuel buildup, etc.) instead of the symptoms (through suppression) leads to more efficient and effective resource management. Implementing these treatments requires a wide range of actions, including timber harvest, biomass utilization, thinning, fuel treatments, and judicious use of prescribed and natural fire” (p. 7).

References

2nd Nature. 2013. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment for the North Coast Integrated Regional Water Management Plan. Report prepared for West Coast Watershed. http://www.2ndnaturellc.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Final-NC-Climate-Change-Vulnerabilty-Assessment.pdf. (August 25, 2016).

Anderson, M. Kat. 2005. Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 558 p.

Barr, B.R.; Koopman, M.E.; Williams, C.D.; Vynne, S.J.; Hamilton, R.; Doppelt, B. 2010. “Preparing For Climate Change In The Klamath Basin.” University of Oregon Climate Leadership Initiative and National Center for Conservation Science and Policy. https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/10722/KlamCFFRep_5-26-10finalLR.pdf?sequence=1. (August 24, 2016).

Bennett, T. M. B.; Maynard, N. G.; Cochran, P.; Gough, R.; Lynn, K.; Maldonado, J.; Voggesser, G.; Wotkyns, S.; Cozzetto, K. 2014. “Indigenous Peoples, Lands, and Resources.” In Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 297-317. doi:10.7930/J09G5JR1.

Briles, C.E., Whitlock, C., Skinner, C.N. and Mohr, J., 2011. Holocene forest development and maintenance on different substrates in the Klamath Mountains, northern California, USA. Ecology, 92(3), pp.590-601.

Bronen, R. 2011. “Climate-Induced Community Relocations: Creating An Adaptive Governance Framework Based In Human Rights Doctrine.” NYU Review of Law and Social Change. 35: 356–406.

Burkett, M. 2011. “The Nation Ex-Situ: On Climate Change, Deterritorialized Nationhood And The Post-Climate Era.” Climate Law. 2: 345–374.

Cameron, E.S. 2012. Securing indigenous politics: a critique of the vulnerability and adaptation approach to the human dimensions of climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Global Environmental Change–Human and Policy Dimensions. 22: 103–114.

Climate and Traditional Knowledges Workgroup [CTKW]. 2014. “Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges in Climate Change Initiatives.” https://climatetkw.wordpress.com/. (August 22, 2016).

Cook, Angelina, Thaler, T., Griffith, G., Crossett, T., Perry, J.A.;. (Eds). 2014. Renew Siskiyou: A Roadmap to Resilience. Model Forest Policy Program in association with the Mount Shasta Bioregional Ecology Center and the Cumberland River Compact; Sagle, ID.

Cuomo, C. 2011. “Climate Change, Vulnerability, And Responsibility.” Hypatia. 26: 690–714.

Donatuto, Jamie; O’Neill, Catherine A. 2010. “Protecting First Foods in the Face of Climate Change— Summary and Call to Action.” Presented at the Coast Salish Gathering Climate Change Summit, July 2010. Can be found as Appendix 4 in the Swinomish Climate Adaptation Action Plan: http://www.swinomish.org/climate_change/Docs/SITC_CC_AdaptationActionPlan_complete.pdf. (August 29, 2016).

GHD, ESA, PWA, Trinity Associates. 2014. “District 1 Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment And Pilot Studies Fhwa Climate Resilience Pilot—Final Report.” Prepared on behalf of Caltrans and Humboldt County Association of Governments. http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/tpp/offices/orip/climate_change/documents/ccps.pdf. (August 29, 2016).

Goodman, Ed. 2000. “Protecting Habitat for Off-reservation Tribal Hunting and Fishing Rights: Tribal Comanagement as a Reserved Right.” Environmental Law 30: 279-362.

Gruenig, Bob; Lynn, Kathy; Voggesser, Garrit; Whyte, Kyle Powys. 2015. “Tribal Climate Change Principles: Responding To Federal Policies And Actions To Address Climate Change.” https://blogs.uoregon.edu/tribalclimate/files/2010/11/Tribal-Climate-Change-Principles_2015-148jghk.pdf. (August 26, 2016).

Hanna, J.M. 2007. “Native Communities And Climate Change: Protecting Tribal Resources As Part Of National Climate Policy.” Boulder, CO: the Natural Resources Law Center, University of Colorado Law School. In conjunction with, the Western Water Assessment at the University of Colorado. http://scholar.law.colorado.edu/books_reports_studies/15/. (August 22, 2016).

Intertribal Timber Council [ITC]. 2013. “Fulfilling The Promise Of The Tribal Forest Protection Act Of 2004—Volume 1.” https://sipnuuk.mukurtu.net/system/files/atoms/file/AFRIFoodSecurity_UCB_SibylDiver_003_003.pdf. (August 29, 2016).

Kronk Warner, Elizabeth Ann. 2015. “Everything Old is New Again: Enforcing Tribal Treaty Provisions to Protect Climate Change Threatened Resources.” University of Kansas School of Law Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2652954. (August 29, 2016).

Lake, Frank. 2007. “Traditional Ecological Knowledge to Develop and Maintain Fire Regimes inNorthwestern California, Klamath-Siskiyou Bioregion: Management and Restoration of Culturally Significant Habitats.” PhD diss., Oregon State University.

Lake, Frank; Tripp, Bill; Reed, Ron. 2010. “The Karuk Tribe, Planetary Stewardship, And World Renewal On The Middle Klamath River, California.” Ecological Society of America Bulletin. 147–149. http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/35556

Lynn, Kathy, Katharine MacKendrick, and Ellen M. Donoghue. 2011.

“Social Vulnerability and Climate Change Synthesis of Literature.” Portland, OR: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

http://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/gpo12563. (August 24, 2016)

Luber, G.; Knowlton, K.; Balbus, J.; Frumkin, H.; Hayden, M.; Hess, J.; McGeehin, M.; Sheats, N.; Backer, L.; Beard, C. B.; Ebi, K. L.; Maibach, E.; Ostfeld, R. S.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Zielinski-Gutiérrez, E.; Ziska, L. 2014. “Human Health.” In Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 220-256. doi:10.7930/J0PN93H5. https://data.globalchange.gov/report/nca3/chapter/human-health. (August 24, 2016).

Maldonado, Julie Koppel; Christine Shearer, Robin Bronen, Kristina Peterson, and Heather Lazrus. 2013. “The Impact of Climate Change on Tribal Communities in the US: Displacement, Relocation, and Human Rights.” Climatic Change (special issue). 120: 601-614.

Marino, Elizabeth. 2012. “The Long History Of Environmental Migration: Assessing Vulnerability Construction And Obstacles To Successful Relocation In Shishmaref, Alaska.” Global Environmental Change. 22:374–381

Mawdsley, Jonathan R.; O’malley, Robin; Ojima, Dennis S. 2009. “A Review of Climate‐Change Adaptation Strategies for Wildlife Management and Biodiversity Conservation.” Conservation Biology. 23: 1080-089.

Norgaard, Kari M. 2014a. “The Politics of Fire and the Social Impacts of Fire Exclusion on the Klamath 1.” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations. 36: 77.

Norgaard, Kari M. 2014b. “Karuk Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Need for Knowledge Sovereignty: Social, Cultural and Economic Impacts of Denied Access to Traditional Management.” Prepared for the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources. http://pages.uoregon.edu/norgaard/pdf/Karuk-TEK-and-the-Need-for-Knowledge-Sovereignty-Norgaard-2014.pdf. (August 23, 2016).

Norgaard, Kari M. 2014c. “Retaining Knowledge Sovereignty: Expanding the Application of Tribal Traditional Knowledge on Forest Lands in the Face of Climate Change. Prepared for the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources.” http://pages.uoregon.edu/norgaard/pdf/Retaining-Knowledge-Sovereignty-Norgaard-2014.pdf. (August 23, 2016).

Norton, Jack. 2013. “If The Truth Be Told: Revising California History as a Moral Objective.” American Behavioral Scientist. 57:1-14.

Olson, D.; DellaSala, D.A.; Noss, R.F.; Strittholt, J.R.; Kass, J.; Koopman, M.E.; Allnutt, T.F. 2012. “Climate Change Refugia For Biodiversity In The Klamath-Siskiyou Ecoregion.” Natural Areas Journal. 32: 65–74.

Risling Baldy, C. 2013. “Why We Gather: Traditional Gathering In Native Northwest California And The Future Of Bio-Cultural Sovereignty.” Ecological Processes. 2:17.

Ruhl, J. B. 2009. “Climate Change Adaptation and the Structural Transformation of Environmental Law.” Environmental Law. Vol. 40, p. 343, 2010; FSU College of Law, Public Law Research Paper No. 406.

Salter, John. 2003. “White Paper On Behalf Of The Karuk Tribe Of California: A Context Statement Concerning The Effect of the Klamath Hydroelectric Project on Traditional Resource Uses and Cultural Patterns of the Karuk People Within the Klamath River Corridor.” http://mkwc.org/old/publications/fisheries/Karuk White Paper.pdf. (August 11, 2016)

Sawyer, J. O. 2007a. Why are the Klamath Mountains and adjacent North Coast floristically diverse. Fremontia, 35(3), 3-11.

Sawyer, J., O. 2007. Forests of Northwestern California. In Barbour, M. G., T. Keeler-Wolf, and A. Schoenherr A., editors. Terrestrial Vegetation of California, .

Shonkoff, S.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Pastor, M.; Sadd, J. 2011. “The Climate Gap: Environmental Health And Equity Implications Of Climate Change And Mitigation Policies In California—A Review Of The Literature.” Climatic Change. 109: 485-503.

Skinner, Carl N.; Taylor, Alan H.; Agee, James K. 2006. “Klamath Mountains bioregion.” In Fire in California’s Ecosystems, N. G. Sugihara, J. W. van Wagtendonk, J. Fites-Kaufmann, K. E. Shaffer, and A. E. Thode, Eds. University of California Press, Berkeley. pp. 170-194.

Stumpff, L.M. 2009. “Climate Change And Tribal Consultation: From Dominance To DéTente.” http://www.georgewright.org/0914stumpff.pdf. (August 24, 2016).

Treaty Indian Tribes in Western Washington [TITWW]. 2011. “Treaty Rights at Risk: Ongoing Habitat Loss, the Decline of the Salmon Resource, and Recommendations for Change.” http://nwifc.org/w/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/08/whitepaper628finalpdf.pdf. (August 22, 2016).

Tsosie, Rebecca A. 2003. “The Conflict between the ‘Public Trust’ and the ‘Indian Trust’ Doctrines: Federal Public Land Policy and Native Nations.” Tulsa Law Review 39: 271.

Tsosie, Rebecca A. 2013. “Climate Change And Indigenous Peoples: Comparative Models Of Sovereignty.” In: Abate RS, Kronk EA (eds) Climate Change And Indigenous Peoples: The Search For Legal Remedies. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 79–95.

Two Rivers Tribune 2016 “Karuk Tribe Holds Its Own Climate Study Session,” Malcolm Terence July 26, 2016 available at: http://www.tworiverstribune.com/2016/07/karuk-tribe-holds-its-own-climate-study-session/

United Nations. 2008. “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf. (August 24, 2016).

U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA]. 2012. “The National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy: Phase III Western Science-Based Risk Analysis Report. Final report of the Western Regional Strategy Committee.” https://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/strategy/documents/reports/phase3/WesternRegionalRiskAnalysisReportNov2012.pdf. (August 23, 2016).

U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA]. 2015. “The Rising Cost of Wildfire Operations: Effect on the Forest Service’s Non-Fire Work.” http://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/2015-Fire-Budget-Report.pdf. (August 23, 2016).

U.S. Department of the Interior [USDI]. 2009. Order No. 3289. https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/migrated/whatwedo/climate/cop15/upload/SecOrder3289.pdf. (August 22, 2016)

Vinyeta, Kirsten; Lynn, Kathy. 2015. “Northwest Forest Plan – The First 20 years (1994-2014) Effectiveness of the Federal-Tribal Relationship.” Report FS/R6/PNW/2015/0005. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 74 p. http://www.reo.gov/monitoring/reports/20yr-report/NWFP – Strengthing the Federal-Tribal Relationship WEB.pdf. (August 24, 2016).

Vinyeta, Kirsten; Powys Whyte, Kyle; Lynn, Kathy. 2015. “Climate Change Through An Intersectional Lens: Gendered Vulnerability And Resilience In Indigenous Communities In The United States.” Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-923. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 72 p. http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr923.pdf. (September 1, 2016).

Western Regional Strategy Committee, 2013. The National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy: Phase III Western Science Based Risk Analysis Report. Final Report of the Western Regional Strategy Committee. Available online at:

http://www.iawfonline.org/WestRAP_Final20130416.pdf

Whittaker, R.H., 1961. Vegetation history of the Pacific Coast states and the” central” significance of the Klamath region. Madrono, 16(1), pp.5-23.

Whyte, K.P. 2013. “Justice Forward: Tribes, Climate Adaptation And Responsibility.” Climatic Change (special issue). http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584- 013-0743-2. (August 22, 2016).

Wiedinmyer, Christine; Hurteau, Matthew D. 2010. “Prescribed Fire as a Means of Reducing Forest Carbon Emissions in the Western United States.” Environmental Science & Technology 44: 1926-32.

Williams, T.; Hardison, P. 2013. “Culture, law, risk and governance: contexts of traditional knowledge in climate change adaptation.” Climatic Change (special issue). http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-013-0850-0. (August 19, 2013).

Wood, Mary Christina. 2014. “Tribal Trustees in Climate Crisis.” American Indian Law Journal. 2: 518-518.

[1] Note that the term “states” here refers to “member states.”

[2] See the USDA’s 2015 Report “The Rising Cost of Wildfire Operations: Effect on the Forest Service’s Non-Fire Work,” available at http://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/2015-Fire-Budget-Report.pdf for details.

[3] E.g. while the Department of Interior has a Secretarial Order on climate change, the Department of Agriculture does not.

[4] This key document has the potential to be a powerful tool for maintaining Tribal sovereignty regarding use of fire and expansion of TEK in the landscape, but has yet to enter policy or regulation. The formal adoption of this idea into policy and regulation would also serve as explicit acknowledgement of Tribal sovereignty and jurisdictional authority over air resources.