In order to maintain a traditional Karuk lifestyle today, you need to be an outlaw, a criminal, and you had better be a good one or you’ll likely end up spending a great portion of your life in prison. The fact of the matter is that it is a criminal act to practice a traditional lifestyle and to maintain traditional cultural practices necessary to manage important food resources or even to practice our religion. If we as Karuk people obey the “laws of nature” and the mandates of our Creator, we are necessarily in violation of the white man’s laws. It is a criminal act to be a Karuk Indian in the 21st century.

–- Leaf Hillman, 2004

Despite the importance of traditional knowledge and management activities for the mid-Klamath ecosystem, the production of healthy Karuk foods, cultural activities, social structure, spirituality and for the physical and mental health of individuals, both the legitimacy of and practical ability of Karuk people to carry out traditional knowledge, management practices and culture on the Klamath have been contested since the arrival of non-Native peoples, and especially since the Gold Rush period of the mid 1800’s (Karuk Social Impact Assessment 2007, Karuk Historical Timeline, 2011). Furthermore, many important activities of traditional management, activities that are from a Karuk perspective necessary for both ecosystem and community health, and for the process of reproducing traditional ecological knowledge, remain either directly illegal under Federal or State laws, or are handled by the agencies in ways that centrally impinge upon their practice. Important steps towards the expanded application of Karuk traditional ecological knowledge and knowledge sovereignty can thus be taken by the agencies merely by removing these barriers to cooperation. Part II of this series will outline these opportunities in more detail.

[Video: Karuk Tribal Members along with Indigenous people from Tolowa Country to the Wiyot Nation express coastal gathering rights in their ancestral territory June 18th 2011.]

As background to communicating the importance of knowledge sovereignty for the Karuk Tribe today, this chapter provides some history and scope of the extent to which knowledge systems and activities have been misunderstood, contested and criminalized. Overt and dramatic disruptions of Karuk management and knowledge systems began with the intensive influx of non-Natives to the mid-Klamath, the failure of the U.S. Congress to ratify the treaties it signed with Karuk people, and the direct genocide of the gold rush era in the 1850s. Yet the period since the establishment of the Klamath National Forest whereby non-Native management practices have been the dominant force in shaping the ecosystem must not be under emphasized. During this time tribal knowledge about ecological processes and conditions has variously been made illegal, ignored, and when incorporated they have been misapplied and taken out of context. As Bill Tripp, of the Karuk Department of Natural Resources notes “Consultation is of course only moderately effective, it depends on who you are talking to, just because you have the Forest Service and Tribe talking together does not mean that such “consultation” is going to be effective.” All too often this program merely serves as a means to check a consultation box or otherwise protect the agency interest. Over the past 10 to 15 years relatively benign factors such as unaware curiosity and a series of misfits between Native and Western worldviews have coupled with lack of understanding and respect to erode the knowledge sovereignty in Native communities and the Karuk Tribe in particular.

Historical Influences on Loss of Knowledge Sovereignty and Traditional Management: Genocide and Forced Assimilation

Major shifts in the Karuk ability to maintain sovereignty over knowledge and cultural practices, tend to food species and the landscape, and carry out daily life began during the gold rush, some 150 years ago. The arrival of miners, the military, and settlers into Karuk territory was accompanied by direct genocide in which many people and much knowledge was lost (Norton 1979, 2013). Violent social dislocation, including the outright killing of three-quarters of Karuk people, the relocation of villages, and attempts to move people onto reservations all interfered with everyday ability of people to survive, much less carry out culture and the practices of tending to the natural world (Lowry 1999, Norton 1979, 2013). In 1851 and 1852, the state of California spent $1 million per year to exterminate native peoples (Chatterjee 1998). Beginning in 1856, the Governor issued a bounty of $0.25 per Indian scalp, increasing it to $5.00 per Indian scalp in 1860 and reimbursed bounty hunters for the cost of ammunition and other supplies. Then, in 1864 the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation was established and all Karuk people were ordered to leave their ancestral lands along the mid-Klamath and lower Salmon rivers and relocate to the reservation. Many people did so. Others fled to the high country or escaped and returned. Yet due to this overt displacement many Karuk people continue to live on the Hoopa reservation, in cities on the coast, and spread across California and Oregon. This dispersal of people had significance for their knowledge sovereignty and cultural practice including people’s ability to participate in cultural activities to tend the landscape.

During this wave of activity actions of gold miners the military and white settlers damaged the ecosystem, restricting the supply of some food sources, including fish and wild game, although they did not initially destroy these populations. This time period marks the beginning of forcible disruption of Karuk land management techniques, especially practices of burning. White settlers and miners did not understand the role of fire in the forest ecosystem with the result that since the gold rush period, Karuk people have been forcibly prevented from setting fires needed to manage the forest, prolong spring run-off, and create proper growing conditions for acorns and other foods (Margolin 1993, Anderson, personal communication). For many years following white settlement in their territory Karuk people were simply shot for engaging in cultural practices such as setting fires (personal communication). Despite these circumstances Karuk people have continued to engage in cultural burns, often at great peril.

[Video: History of traditional burning becoming illegal on the Klamath and across the Western United States. Watch the entire film here]

A second significant factor affecting knowledge sovereignty concerns the lack of recognition of land title. In 1851 the U.S. government negotiated a treaty with the Karuk Tribe (Hurtado 1988). White landowners across what had just become the state of California however found the treaties unappealing as they gave Indians land, flour, pack animals, dairy cattle, and beef cattle which would likely mean Native people would work their own ranches instead of providing cheap labor. “Treaties that conflicted with agriculture and mining interests had little hope of finding support in California’s state government” which “did everything possible to thwart them” (Hurtado 1988:139-40). On July 8, 1852, due to pressure from the Governor of California, Congress refused to ratify this and other California treaties of that time. As a result, 18 California tribes, including the Karuk, who had agreed to treaty terms in good faith, were left without any of the protections, land or rights they reserved in their treaties (Hurtado 1988).

A third historical factor behind the loss of knowledge sovereignty and ability to carry out Karuk management practices in the forest was the period of forced assimilation to the dominant culture through boarding schools and other institutional processes.  Like youth from tribes throughout Canada and the United States, Karuk children were separated from families at young ages and taken to boarding schools in Oregon and elsewhere for the specific purpose of assimilation. They were prevented from speaking Karuk, from practicing Karuk customs and forced to eat a diet of “Western” foods. The result was that Karuk children were separated from their families, traditions and their ancestral territory often for years, and were unable to learn fishing, gathering and management practices or cultural ceremonies.

Like youth from tribes throughout Canada and the United States, Karuk children were separated from families at young ages and taken to boarding schools in Oregon and elsewhere for the specific purpose of assimilation. They were prevented from speaking Karuk, from practicing Karuk customs and forced to eat a diet of “Western” foods. The result was that Karuk children were separated from their families, traditions and their ancestral territory often for years, and were unable to learn fishing, gathering and management practices or cultural ceremonies.

Criminalization and Restriction of Management Activities Today

Today knowledge sovereignty for the Karuk and many other Native people is threatened by the criminalization of the traditional cultural activities that are necessary for its regeneration. Activities including the gathering acorns, mushrooms, berries, basketry materials, and the use of fire to create the proper conditions for these species use, today remain either illegal under Forest Service law, or are regulated by the agency in ways that limit or prohibit Karuk access. For example, many foods and numerous cultural use species are enhanced by burning. Burning is directly necessary to produce the correct kinds of shoots for weaving, as well as to keep materials in adequate condition. Karuk Cultural Biologist Ron Reed describes the holistic system of burning.

Hazel sticks. Photo: Frank Lake

You have deer meat, elk and a lot of times associated with those acorn groves are riparian plants such as hazel, mock orange or other foods and fibers, materials in there that prefer fire. The use of those materials is dependent upon those prescribed burns. So when you don’t have those prescribed burns it affects all that in a reciprocal manner. It’s a holistic process where one impact has a rippling effect throughout the landscape. We can only have that for a certain amount of time before the place becomes a desert without cultural burns, because the plants are no longer soft and the shoots are no longer food, instead they become these intermediate stages where they are just taking up light and water and tinder for catastrophic fire. So it has an impact not only on the species we are talking about, but how you harvest and manage and hunt those species as well.

Non-Indian fishing regulations, such as those developed and enforced through California Department of Fish and Wildlife, have often failed to take into account the Karuk as original inhabitants, their inalienable right to subsistence harvesting and the sustainable nature of Karuk harvests. As a result they have attempted to balance the subsistence needs of Karuk people with recreational desires of non-Indians from outside the area. Karuk tribal member Vera Davis notes the imbalance and injustice of this view:

Now I don’t think that no one has a right to tell us when we can do it when you have people who pay hundreds of dollars to come in, kill the venison and get the horns. I don’t think that is fair because this is our livelihood . . . We had supplies from the river the year round. We hadn’t been told that we couldn’t get our fish any time of the year. That was put there for us by the Creator and when we were hungry we went to the river and got our fish. -Vera Davis (quoted in Salter 2003, p.32)

However, hunting regulations are set by the State of California according to “white man’s” rather than tribal law. If a Karuk person hunts “out of season” or gets a deer without purchasing a tag from the State it is considered poaching. Getting caught for poaching has a variety of consequences depending on the circumstances and if it is a repeated offense. Director of the Karuk Department of Natural Resources and Ceremonial Leader, Leaf Hillman describes this situation:

“The act of harvesting a deer or elk to be consumed by those in attendance at a tribal ceremony was once considered an honorable, almost heroic act. Great admiration, respect and celebration accompanied these acts and those who performed them. Now these acts (if they are to be done at all) must be done in great secrecy, and often in violation of Karuk custom, in order to avoid serious consequences.”

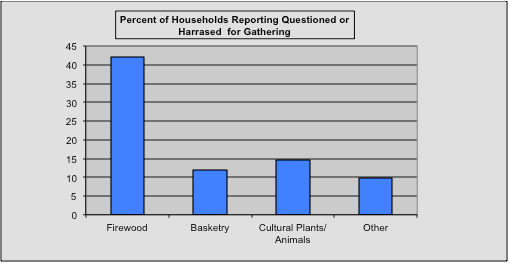

As Hillman explains it, government regulations force assimilation to the point of criminal indictment. While there are provisions for some forms of subsistence gathering through Forest Service policy, in the 2005 Karuk Health and Fish Consumption Survey tribal members were asked whether members of their household had been questioned or harassed by game wardens while gathering a variety of other cultural and subsistence items. As indicated below, 12 percent reported such contacts while gathering basketry materials and over 40 percent while gathering firewood. Twenty percentage of survey respondents reported that they had decreased their subsistence or ceremonial activities as a result of such contacts. To be fined or have a family member imprisoned imposes a significant economic burden on families. This is a risk that many are unwilling or unable to take.

In the words of traditional dipnet fisherman and spiritual leader Kenneth Brink

Karuk men dipnet fishing at Ishi Pishi Falls. [Read Los Angeles Times Article from 2002: Tribe Forgoes Law in Quest for Salmon]

Karuk Tribal member and spiritual leader Achviivich notes “Our way of lives has been taken away from us. We can no longer gather the food that we gathered. We have pretty much lost the ability to gather those foods and to manage the land the way our ancestors managed the land.” Karuk tribal member Jesse Goodwin explains how “usually, they just take our gun rights away from us, try to see if there’s any way of us never being able to do it again, and then after that they send you to jail.” Tribal member Mike Polmateer explains the reality of growing up under these circumstances:

When I hunted with my uncles, for the longest time I never knew you hunted during the day. We always went and got our meat at night. And it was always about where’s the game warden, you know, where’s the cops, and you know, things like that. So that’s one of the things that stuck in my mind as a young kid. We were always watching for headlights, you know, always trying to hide from the law, out doing what we were supposed to do, which was provide for our families. We weren’t out selling meat. We weren’t out selling hides.

In the 2005 Karuk Health and Fish Consumption Survey tribal members were also asked whether members of their household had been questioned or harassed by game wardens while gathering a variety of other cultural and subsistence items. Twelve percent reported such contacts while gathering basketry materials, and over 40 percent indicated harassment while gathering firewood. Twenty percent of survey respondents reported that they had decreased their subsistence or ceremonial activities as a result of such contacts.

The lack of recognition of land title is coupled with a lack of recognition of fishing rights. Whereas long standing cultural traditions existed for regulating and sharing fish and other resources both within the Karuk Tribe and between neighboring tribes, the entry of non-Indian groups into the region led to conflict and dramatic resource depletion (McEvoy 1986). During the 1970’s the Federal government stepped up enforcement and forcibly denied Karuk people the right to continue their traditional fishing practices (Norton 1979) by arresting them and even incarcerating them. Karuk fishing rights have yet to be acknowledged by the U.S. government, though now tribal members may fish at one ‘ceremonial fishery.’ As tribal member Jesse Coon explains

We can fish at the falls. Dipnet and that, you know, that’s the only place we can fish really. But we’re not able to go out and go hunting anymore, without getting in trouble for it or something, you know, so—now we have to go to the store to buy our food, and get different kind of foods that aren’t sustainable for our bodies, like food that was made here for our people, you know? So a lot of it has changed that way, you know….

Access to food and notions of how land should be used may be contested, but the state holds the ability to assert its version. Traditional Karuk Fisherman Mike Polmateer describes his experience fishing at his family’s long-established site:

I fish at my family’s hole up here at Dillon Creek every single day during the winter, and I’m checked for my license no less than six times per year, by the same game warden, by the same two game wardens over and over and over, trying to catch me keeping fish. They sit up here on a point with binoculars watching me catch fish, and they watch me return them to the water. Because I’m—I’m afraid . . . There’s consequences to be suffered . . . If you send your child out in to the world right now not knowing there’s consequences to be suffered, they’re going to end up like many many natives, not only in this country but in other countries, in the penal system. What I’m seeing now is this penal system is—they’re raising our young kids now. They’re going in at 18, 19, 20 years old, not coming out until they’re 27, 28, 30 years old.

Tan oak mushroom. Photo: Klamath-Salmon Media Collaborative

Regulations affect not only fishing but also hunting, mushroom gathering and gathering of basketry materials. Karuk Tribal member and spiritual leader Achviivich explains how in the face of degraded forest conditions due to fire exclusion and possible harassment by law enforcement many people give up hunting and buy store bought foods instead:

How much society’s laws are preventing me from gathering? Well, 80% 90% . . . do I want to go out there and be hassled about it? Why? I go down to the damn store and buy that stuff a lot, you know. It is going to cost you more to go hunt, to go out into the woods and get it. It is not like it is readily available no more. It is not like you have a gathering spot like we used to have a gathering spot. You know, you used to have a gathering spot to gather something and you would go there and gather. Now you don’t. Now you can’t burn there. You can’t burn there every year and every other year or however often you need to burn it in order to make your crop come up good. You can’t do that. You can’t burn. And you have to have a permit to get everything. Everything. You have to get a permit to get rocks off the god damn river bar out here. Did you know that?

Dried tan oak mushrooms. Photo: Klamath-Salmon Media Collaborative

Karuk cultural ecological knowledge is lost when the above actions of the state deny Karuk people access to the land and food resources needed to sustain culture and livelihood. Forced assimilation happens even more overtly when for example game wardens arrest tribal members for fishing according to tribal custom rather than state regulation. Karuk Tribal member and spiritual leader Achviivich describes an example of the significant use of force that can be applied for minor infractions:

Here was a tribal member, two tribal members right up there and they had them sprawled on the ground with a gun on their, on the back of their head because they didn’t cut their mushrooms in half.

Denied access to traditional management at the hands of non-native agencies has significant health, cultural and spiritual impacts including denying them access to healthy foods (see Jackson 2005, Norgaard 2005). Yet Karuk lifeways continue to be practiced both overtly (when they can get away with it) and covertly when they cannot. From a Karuk perspective, continuance of these traditional lifeways and practices is essential not only for food, but for the maintenance of traditional knowledge, cultural and tribal identity, pride, self-respect and above all, basic human dignity. Thus, while non-Tribal agencies have attempted to gain access to Karuk knowledge, a far more effective and appropriate action these agencies can take is to remove the barriers their policies put into place. Part Two of this report series is devoted to detailing these opportunities.