Healthy Foods and Physical Health

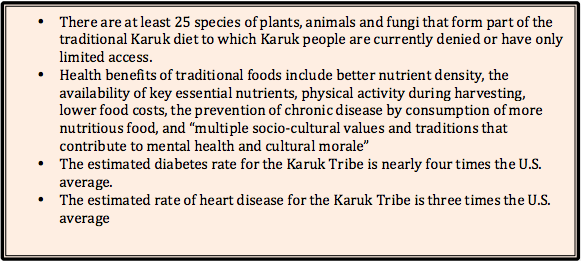

Today in the face of the altered ecology of the mid-Klamath region Karuk people face significant health consequences as a result of denied access to many of their traditional foods (Norgaard 2005). This chapter will survey the importance of changes in the ability of Karuk people to carry out traditional management on their physical health. These include access to the direct benefits of traditional foods from the forest, and the exercise that comes from participation on these activities. Health benefits of traditional foods include better nutrient density, the availability of key essential nutrients, physical activity during harvesting, lower food costs, the prevention of chronic disease by consumption of more nutritious food, and “multiple socio-cultural values and traditions that contribute to mental health and cultural morale” (Kuhnlein and Chan 2000, 615; Cantrell 2001). The loss of traditional food sources is now recognized as being directly responsible for a host of diet related illnesses among Native Americans including diabetes, obesity, heart disease, tuberculosis, hypertension, kidney troubles and strokes (Joe and Young 1994).

Around the world when Native people move to a “Western” diet rates of these diseases skyrocket. Traditional foods are higher in protein, iron, zinc, omega-3 fatty acids and other minerals and lower in saturated fats and sugar. While salmon and other riverine foods have been an important focus of past work on Karuk diet and health, there are at least 25 species of plants, animals and fungi that form part of the traditional Karuk diet to which Karuk people are currently denied or have only limited access as a result of their decline in over the past 150 years of non-Native management, or because regulations prohibit or limit access. It is especially notable that salmon and tan oak acorns, which historically provided the bulk of energy and protein are amongst the missing elements. Identified health consequences of altered diet for the Karuk people include rates of Type II diabetes that are four times the U.S. average and heart disease at three times the U.S. average (Norgaard 2005, 2007). A traditional diet and the exercise entailed in procuring it are widely recognized as both the best prevention and the best treatments for these “diet related” conditions.

[Slideshow: River youth prepare and enjoy traditional foods. Photos: Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources and Klamath-Salmon Media Collaborative]

While rates of heart disease are decreasing in the general U.S. population, they are on the rise for Native Americans. Rates of strokes are also higher for Indian people. Other associated conditions such as obesity result from decreased nutrition. Obesity is an issue not only of altered diet, but of a sedentary lifestyle far removed from traditional food gathering practices. Nationally high rates of infant mortality for Native peoples are also linked to nutritional deficits. Nutritional data indicate that women with diets containing adequate protein experience fewer spontaneous abortions, premature births and healthier infants. Indian Health Services reports that the infant mortality rate for Native Americans is 21 times the national average (CRIHB 2004). Finally, as a result of the high prevalence of these diseases, Native people in the U.S. have an average life expectancy that is six years lower than the general population and the lowest median age in the United States (ibid). Given the dramatic change in diet and high incidence of diabetes and heart conditions in the Karuk Tribe, high incidence of the conditions mentioned above are also suspected.

These changes in access to traditional foods have occurred during the lifespan of most adults alive today. In the Karuk Health and Fish Consumption Survey nearly 40 percent of respondents report eating meals with traditional foods once a week or more as a teenager, and another 25 percent once a day or more. Only about 7 percent indicated that they never ate traditional foods. In contrast, today less than 5 percent reported eating traditional foods on a daily basis, and only 17 percent reported eating traditional foods once a week or more (note that these numbers are still very high when compared with non-Native consumption of such foods). The number of people who report never eating traditional foods rose from 6 percent as a teenager to 22 percent today.

Not only does a traditional diet prevent the onset of conditions such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, kidney trouble and hypertension, the tasks of acquiring traditional food provided exercise that kept people in good physical condition. There are other relationships between physical health and access in the altered forest structure. As ecologist and Karuk Descendant Frank Lake describes a brushy understory creates significant dust which is itself a health hazard:

There is a related health issues there, and I had to explain this to the firefighters just recently [summer 2008]. When there is a big clear understory and a big acorn tree with the firs and madrones mixed around. Before, you didn’t have that underbrush, that younger growth of the tan oak has this kind of dust on it. And it is particularly more so on the new sprouts, the new shoots and the new leaves. So as you are going through that tan oak understory, that thick brush, you are getting that dust in your nasal cavities and your eyes and your throat. So it is actually causing additional problems. Whereas if they could just clear the understory brush out, cut it down and pile burn or even broadcast, burn the understory, it would actually reduce that part of that tan oak dust being an irritant and a potential health problem that is associated with trying to go out there and collect.

–Dr. Frank Lake, Wildlife Resource Advisor, USFS

[Video: Tan oak trees after a controlled burn at Butler Creek]